When art would change the world: the story of British conceptualism

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Congratulations to Andrew Wilson. Tate Britain’s Modern and Contemporary curator has pulled a minimalist rabbit out of a conceptual hat in his new exhibition, Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979. It is ascetic, elegant, and paced as unpredictably as a Bach Cello Suite rearranged by John Cage. Wilson has orchestrated our journey around grids of photographs, documents, vitrines and a handful of black-and-white paintings and installations. Ostensibly this is a story about British conceptual art but it feels more like a homage to Frank Stella, Donald Judd and Agnes Martin.

Thank goodness. In serving up the knotty conundrums of artists such as Stephen Willats, Keith Arnatt and the Art & Language collective in such a mouthwatering way, Wilson has rendered palatable a moment that can feel distinctly arid.

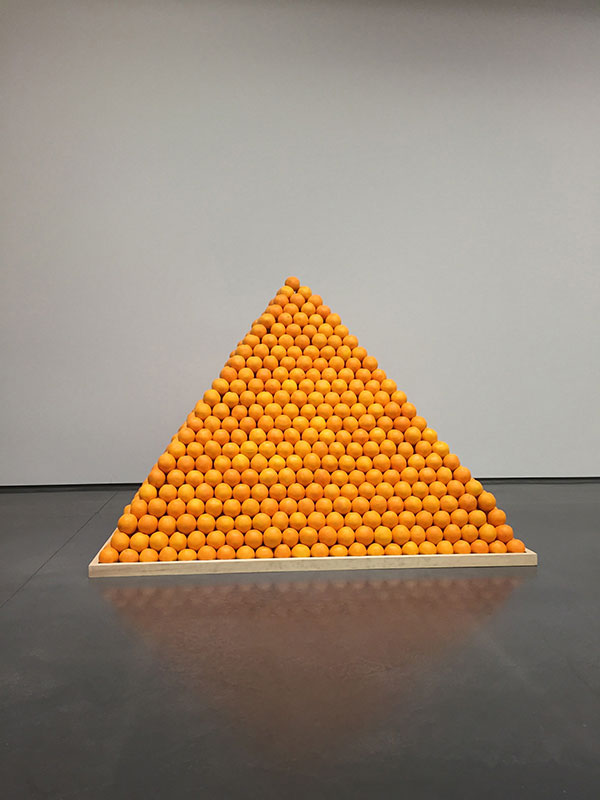

Although most of this show is as sensuously monochrome as a French art-house movie, it was a wise decision to centre the first room on the pyramid of oranges assembled in 1967 by Roelof Louw. Entitled “Soul City”, its buoyant glow reassures us that there’s mischief in the mental gymnastics to come.

Yet it also reminds us of the classical foundations that the conceptualists were so keen to dismantle. From the Egyptians, by way of Plato’s solids, the Renaissance masters and 20th-century geometric abstraction — not to mention the oranges beloved of still-life giants such as Cézanne — those mathematical lines act as both praise-song and parody of Louw’s elders.

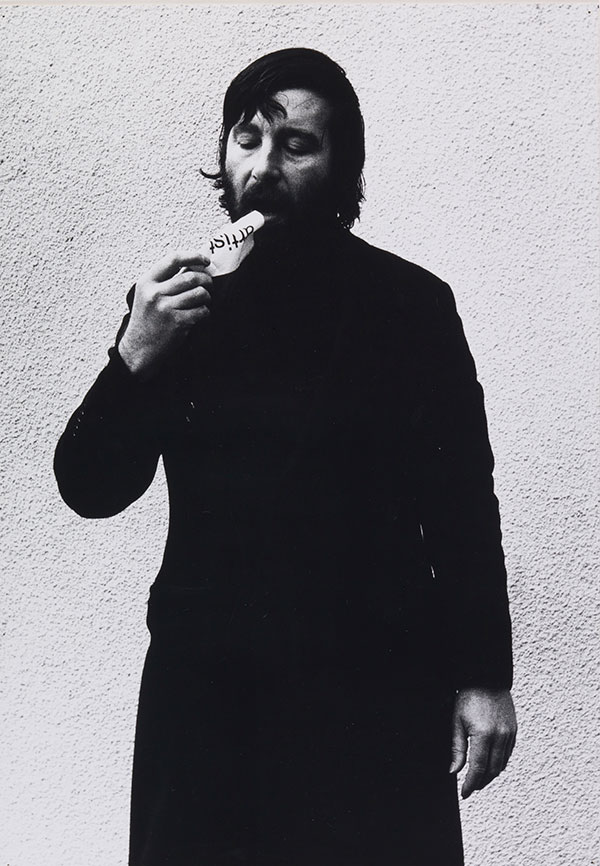

Public enemy number one was American critic Clement Greenberg. The mandarin of high Modernism had, so the Young Turks believed, corralled art into an endgame that could be played out only between painting and sculpture. Crucible of the ferment was London’s Saint Martins School of Art. Here, tutor John Latham went so far as to tear out pages from a copy of Greenberg’s collection of essays Art and Culture. After his students chewed them to a pulp, Latham stirred the papers up with chemicals until they bubbled, before displaying the flask in an attaché case.

At Tate, we have just a black-and-white photograph of the bottle. Yet this meek object encapsulates the combustible forces — from Andy Warhol to the anti-Vietnam protests — that made the 1960s a catalyst for irrevocable change.

At Saint Martins, the new winds of freedom blew philosophy, cybernetics and theories of perception on to the syllabus alongside old-fashioned painting and sculpture. Art was no longer about making. It was about thinking, questioning and deconstructing.

Louw encouraged spectators to take away his citrus fruits, thereby suggesting art could be mutable and participatory. Keith Arnatt — “Invisible Hole Revealed by the Shadow of the Artist” (1968) — dug a square in a lawn, covered the bottom with grass, lined the pit with mirrors then photographed his shadow falling over it, without which the depth would have been imperceptible. That art is, on one level, always a game of smoke and mirrors is underscored by a 1966-67 work in the first room by Art & Language: two rectangles in grey paint bearing the legends “Painting” on one and “Sculpture” on the other.

Art & Language were the true puritans of British conceptualism: their work rarely permitted so much as a shiver of sensory delectation. Their fluid posse included David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin, Terry Atkinson, Mel Ramsden and Joseph Kosuth. Their lair was Coventry College of Art, where Atkinson, Bainbridge and Baldwin taught, and their vision was fuelled by the idea that art was as much about the words that defined it as its material substance. Wilson devotes the second room to their spartan meditations. Don’t be daunted by the vitrines filled with volumes of their journal Art-Language (home to such enticing essays as “Aspects of Authority”). Instead, enjoy their more ludic side, such as “Secret Painting” (1967-68), a black canvas accessorised by a text telling us that “the content of this painting is invisible . . . [it is] known only to the artist”.

In our post-postmodern era, such Saussurean shenanigans have lost their sting. But at the time, Art & Language were breaking new ground by illuminating the systems of power that keep the art world turning. For example, who defines the art work? The artist? Or the institution that writes the label that goes next to it? And how many of us spend more time reading the text panels than looking at the work itself?

The third and fourth rooms consider the institutionalisation of a genre whose subversiveness was supposed to help it resist such a fate. In reality, the ease with which performances could be documented through photographs made it easy, as this show’s sumptuous matrices testify, to cage the conceptual beast.

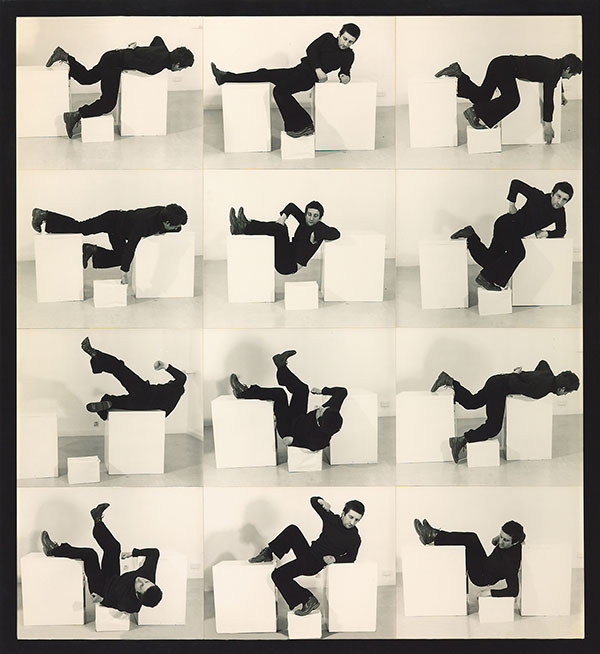

In the UK, the spotlight was shone on conceptualism by two major exhibitions: When Attitudes Become Form at the ICA in 1969 and Seven Exhibitions at Tate Gallery in 1972. A Beckettian base note of tragicomedy animates the offerings of many participants. Two suites of black-and-white photographs show Keith Arnatt eating his own words — he munches pieces of paper on which he scribbled — and burying himself in a hole in the rural hills. Bruce McLean, meanwhile, takes a pop at Anthony Caro’s lily-livered approach to the avant-garde. As Caro thought it so bold to topple sculpture from its classical plinth, McLean photographed himself as a living statue tumbling about between white display blocks.

There was a third way between the deserts of theory and the theatre of the absurd. In the most spacious room here, the chord of Romanticism that hummed through the movement is heard loud and clear. It’s most evident in the work of Richard Long. Scattered throughout the exhibition, photographs of the land artist’s unkempt Arcadias, accompanied by his lyrical word maps, cannot but summon the ghosts of Wordsworth, Caspar David Friedrich and Ansel Adams.

Made in 1972, “The Spring Recordings” by David Tremlett is as beautifully structured as a Shakespearean sonnet. Born when he travelled through every county in Britain making tape recordings of sounds heard en route — often just birdsong and the cry of the wind — the piece distils this potentially sentimental exercise into a row of boxed tapes mounted on bracket shelves.

Running along a three-dimensional grid painting, the installation’s mute, less-is-more rigour reminds one of a sculpture by Donald Judd, who influenced many British conceptualists, and enjoys an extra stratum of spontaneity thanks to the way it casts its immaculate replica in shadow on the wall.

By the mid-1970s, as socialism crumpled in Britain’s public sphere, artists translated their theories of democracy into a more activist practice. The final room is a welcome reminder of this earnest, innocent moment when British artists genuinely believed their art might change their world. Encapsulated by Victor Burgin’s bitterly ironic poster of a glamorous couple embracing above the tagline “7 per cent of our population own 84 per cent of our wealth”, these works ride a wave of anger fuelled by the burgeoning inequality now embedded in Britain’s faultlines.

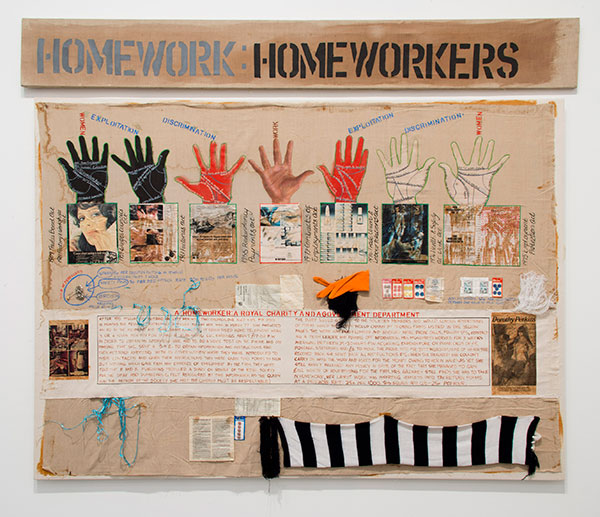

Meanwhile, a new band of feminists such as Margaret Harrison, present here with “Homeworkers” (1977), her sardonic collage of glossy magazines, sewing materials and rubber gloves, made work out of the revelation that for women, the personal was political. It’s an education, too, to see Conrad Atkinson’s impeccable wall piece “Northern Ireland 1968-May Day 1975”, where photographs and slogans from Loyalist, Republican and British army factions winkle out the humanity within every element of that bloodstained triad.

Atkinson’s work raises the question of why more artists haven’t made work about the Troubles. But British conceptualism’s political wing soon crashed to earth. Brought down by Thatcher’s Britain, its legacy flutters in the less-ordinary Young British Artists such as Mark Wallinger. It’s sad to think that Duchamp’s baton has been held aloft most famously by Damien Hirst, for it was the Frenchman’s wand that essentially waved conceptualism into being. Perhaps Hirst thought Burgin’s poster was a call to action. If you can’t beat the rich, you might as well join them.

To August 29. tate.org.uk

Photographs: Tate/Bruce McLean/Tanya Leighton Gallery; Aspen Art Museum; Tate/Keith Arnatt Estate; Tate; Tate/Keith Arnatt Estate/DACS

Comments