China’s mountain to climb — 2022 Winter Olympics

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

As you fly into Beijing you can look out the window of the aeroplane and — as long as there is a strong wind to blow away the smog — see little strips of white, like Band-Aids stuck on to the brown, desolate rump of northern China. These little ribbons of man-made snow are what pass for ski fields in the place that has just won the right to host the 2022 Winter Olympics.

I have been skiing and snowboarding in China since I first arrived in the country in 2000 but the news that Beijing will host the games in seven years’ time left me, and many people I know, a bit conflicted. There is the question of China’s awful human rights record, which prompted campaign groups to denounce the International Olympic Committee’s decision to make Beijing the first city ever to host both the summer and winter Games. Environmentalists are also outraged, since most of the snow in 2022 will be man-made, with snow-making predicted to consume more than 1 per cent of the water supply of Beijing, which already suffers from drought.

The lack of precipitation, despite temperatures that are below freezing, presents the biggest practical problem for the Games. Chinese Communist party officials in charge of the city’s Olympic bid have proudly proclaimed that the mountains outside Beijing where outdoor events will be held received a grand total snowfall of 20-70cm during the last ski season. The 2010 Vancouver Olympics were criticised for their lack of snow even though Whistler mountain, where most outdoor events were held, gets more than 11 metres in an average winter — almost 16 times the total for Beijing’s mountains.

While the Chinese ski industry has come a long way in the last 15 years in terms of facilities and investment, it is still light years behind most other places, particularly when it comes to basic service standards and, most importantly, safety and medical facilities. But perhaps the focus and investment that comes from hosting an Olympics will prompt the industry to get its act together and help nurture some of the services, soul and spirit still missing from winter sports in China.

I started skiing when I was eight years old on an active volcano in the middle of New Zealand’s north island and I have been a member of my high-school ski team, a volunteer ski patrol, a ski bum in Canada and the US Pacific Northwest, and a snowboard instructor in Colorado.

So at the start of 2000 when I moved to Manchuria in north-east China, where temperatures drop below minus-30C in winter, I naturally decided to take an old snowboard with me.

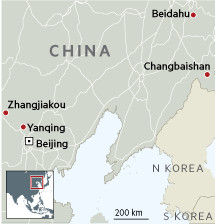

My first outing was to Beidahu in Jilin Province, which the internet told me was China’s best ski resort and the place where its Olympic team trained. But when we finally arrived in a battered old taxi, the facilities were a shock after the comforts of western resorts.

We ignored the decrepit, overpriced Soviet hotel at the base of the ski lifts and opted instead for a local restaurant where my two friends and I ate and slept in a room built over a kang — a traditional stone bed, heated from below by a fire. Large glass jars of potent liquor containing exotic flora and fauna — from red ants to deers’ penises — helped us build up the courage to visit the open-air toilet. This was nothing more than a couple of planks raised above a pile of frozen excrement that melted briefly on contact with any fresh contributions, releasing a nauseating gust of methane before refreezing.

Apart from a family of South Korean novices, the ski field was deserted, even though conditions were perfect and we could see steep trails of fresh powder winding up the wooded hills. The ski-field employees were excited about my snowboard, which they said was only the second they had ever seen, and after a bit of haggling they agreed to open the ancient lifts for a “fee” they said was to cover electricity but which actually went in their pockets.

Today, Beidahu has new lifts and much better infrastructure but the freezing temperatures, lack of fresh snow and huge crowds of beginners make it far less pleasant than that afternoon of nonstop tracks on 10cm of fresh powder 15 years ago. I have been skiing and snowboarding in China dozens of times since then, at new resorts with state-of-the-art gondolas and snow-making machines, but only one other China ski experience comes close to matching it.

Last year I went with some well-connected Chinese friends to Changbaishan on the border with North Korea, where we risked avalanche and trigger-happy border patrols to immerse ourselves in “white opium”, as hardcore Chinese skiers like to refer to snow. The on-piste skiing at the “resort” consisted of little more than a trail of hard-packed ice that had to be shared with oncoming traffic: reckless snowmobile drivers whipping around blind corners carrying communist officials up the hill. But a short hike beyond the warning signs and ski-field boundary over the back of the peak took us into a huge steep bowl where we spent most of the day cutting fresh tracks on fluffy fresh powder. This trip was around Easter and coincided with the last snowfall of the season, which was followed by crystal blue skies and uncharacteristic warmth. But for most Chinese skiers, the experience is somewhat different.

“There is no culture of skiing in China; the first ski areas emerged in the 1980s, mostly designed for the training of ski racers, with usually only one slope and poor accommodation,” says Laurent Vanat, a consultant focused on the international skiing industry. “People in China consume skiing as a leisure activity like they are going bowling.”

In good old-fashioned communist style, President Xi Jinping has decreed that the 2022 Olympics will inspire 300m Chinese to take up winter sports. Hitting targets is something the country’s rulers are usually quite good at but this one may be a stretch — the number of ski visits each year is currently estimated at around 12m.

Of those, the vast majority go for less than a day, with fewer than 300,000 people taking an overnight ski trip and just over 20,000 people each year staying for more than a week, according to Benny Wu, who runs ski resort operational management at Wanda Cultural Industry Group, a subsidiary of one of China’s largest property developers.

A year ago China had an estimated 350 ski resorts but this coming season there are expected to be around 450, as local governments all over the country try to cash in on the boost from the Winter Olympics. Facilities have improved a bit since my early days at Beidahu but, according to Vanat, fewer than 20 of China’s resorts come anywhere close to western or Japanese industry standards.

Unfortunately, such rapid expansion and the fact most people are beginners makes skiing in China even more dangerous than elsewhere. If you’ve ever had the misfortune to injure yourself on the slopes, you’ll know that ski towns in the west boast some of the world’s best fracture clinics and emergency services.

If you get hurt skiing in China, the most you can hope for is a teenage kid in a ski patrol jacket who dumps you into a stretcher sled and deposits you near the car park, so that you can drive yourself to a hospital where your chances of adequate medical care are slim.

Two Christmases ago, my family experienced this first-hand when a hugely overweight beginner skier hurtled down the hill and collided with my wife as she neared the end of her last run of the day. We were at one of the small resorts in Chongli county — now known in Olympic parlance as the Zhangjiakou Zone, where snowboarding and freestyle events will take place. Our experience of the emergency services there made us decide never to go on a family ski trip in China again.

My wife was taken by sled in agony to a small clinic where the doctor said there was nothing he could do for her. He suggested we drive ourselves to the closest medical facility — a traditional Chinese medicine hospital half an hour’s drive down a bumpy dirt road.

When we arrived, the person on duty made us wait for half an hour before turning on the ancient X-ray machine and examining the image upside-down, announcing that the intense pain in my wife’s rib cage had been caused by nothing more than a minor bruise. (The following day we visited a hospital in Beijing, where doctors confirmed she had a badly broken rib.)

We tried not to think what would have happened if the injury had been more serious. Ambulances are scarce outside China’s largest cities, while helicopters are banned by the military, so rapid evacuation for life-threatening injuries is impossible. If the Winter Olympics at least bring proper investment in alpine emergency services, then most people I know will consider the Games a success.

Additional reporting by Christian Shepherd

The road back to Beijing

When Olympic officials announced Beijing’s victory on July 31, it was the culmination of a long and troubled bidding process. Back in 2013, the Olympic committees of six countries made official applications to host the Games: Norway, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Poland, Sweden and China. But rather than backing their national bids and striving for the honour of hosting, politicians and the public in several countries were soon campaigning to be spared the event.

In January 2014, Stockholm announced it was ditching the Swedish bid over cost concerns. In May, Krakow responded to a public campaign against the Games by holding a referendum on whether to proceed with the bid; 70 per cent of residents said no. Ukraine withdrew its bid after the conflict broke out.

Much opposition stemmed from the scale of investment, with fears increased by Russia’s record $51bn spend on the Sochi Games. A Winter Olympics, with many events taking place in mountain villages with limited accommodation, can be harder to convert into an immediate tourism boost than a summer one.

But others were apparently put off by the perceived high-handedness of Olympic officials. Norway — previous host of two successful Games and winner of more Winter Olympic medals than any other nation — cancelled Oslo’s bid in October last year, with prime minister Erna Solberg citing a lack of public support. VG, one of Norway’s largest newspapers, had published a list of demands from officials, including a cocktail reception with the king and special lanes for Olympic traffic. “These insane demands that they should be treated like the King of Saudi Arabia just won’t fly with the Norwegian public,” wrote the paper’s chief political commentator. That left only two contenders: Almaty in Kazakhstan, and Beijing.

Photographs: Simon Song; John Huet; Shen Du; EPA

Comments