US autos: Adding new routes

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The low-rise brick buildings on Ford Motor’s River Rouge site, in Dearborn, Michigan, would still be recognisable to Henry Ford, the company’s founder, who masterminded the facility that opened in 1928.

A vast steel mill dominates the skyline, a reminder of Ford’s vision that the plant would take in iron ore at one end and disgorge Ford Model As at the other. Vehicles are still rolling out at River Rouge, where the Dearborn truck plant produces the hugely profitable F-150 pick-up truck. Thousands of gleaming trucks wait on railcars to be shipped to auto dealers around the US.

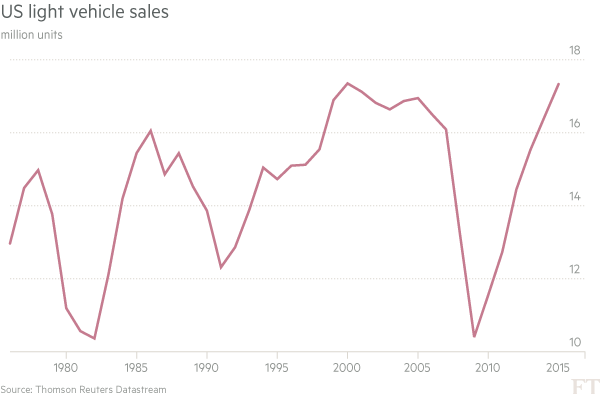

As the busy scene at River Rouge attests, the auto industry in North America is doing extraordinarily well at selling old-fashioned, petroleum-fuelled vehicles. Carmakers in the US last year sold 17.33m cars, trucks and sport utility vehicles, close to the all-time record. Ford, the US’s second-biggest carmaker, consistently sells more than 60,000 F-150s — North America’s best-selling vehicle — a month in its home market.

Yet, despite the success of its current way of doing things, the mainstream US auto industry is preparing for a future that Henry Ford could scarcely have imagined. A short drive away from the F-150 plant, at Ford’s product development centre, the focus is on innovation. In one area, engineers are developing self-driving cars. Elsewhere, staff are tinkering with bicycles, assessing whether they might have a role in Ford’s product range. Most shockingly of all, Ford’s engineers are no longer encouraged to drive company cars around the campus. Instead they call up a GoRide shuttle bus using an app on their smartphones.

The initiatives are part of the response to a surge of interest in the auto industry from technology companies like Google, ride-hailing start-ups like Uber and electric carmakers like Tesla. All aim to transform how cars are driven or owned.

Ford and its longtime rival, General Motors, the US’s top-selling carmaker, are determined not to find themselves outflanked in the battle to develop vehicles that can drive themselves, are connected to the internet and are electrified. Instead of thinking of themselves merely as car manufacturers, they are rebranding themselves as providers of all-round transport services.

“I believe the auto industry will change more in the next five to 10 years than it has in the last 50,” Mary Barra, General Motors’ chief executive, is fond of saying.

Yet it remains unclear whether the industry can change as fast as the bullish projections suggest, whether there is a commercial case to do so, and whether in the attempt to transform themselves the big carmakers risk neglecting the traditional market that still provides nearly all their sales.

Owner-driver overhaul

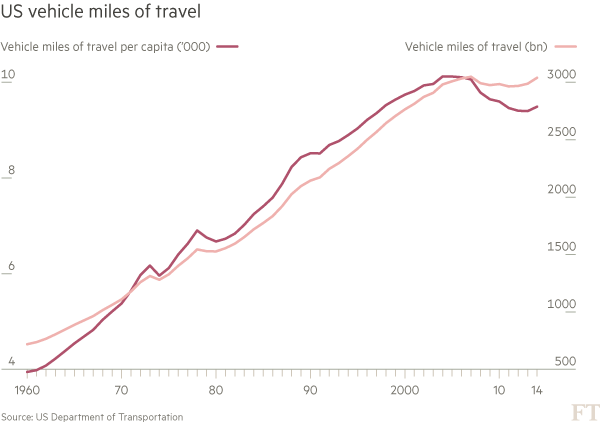

Raj Nair, Ford’s head of product development, acknowledges that the company will need new products and services as it faces some long-term challenges. Among them is a steady decline over the past 15 years in the number of vehicles sold per person in the US.

“All the societal trends, all the economic trends . . . are reasons [why] we know what we sell today and put out to the market today could be significantly expanded tomorrow,” he says.

Chuck Stevens, GM’s chief financial officer, says the change to the existing business will not be rapid or immediate. But he predicts that, as cars take over more of the driving from humans and electrification and ride-hailing increase, traditional patterns of vehicle ownership will break down.

“We do firmly believe that the traditional owner-driver model will change over time,” he says.

Yet some sceptics, including Sean McAlinden, chief economist at the Michigan-based Center for Automotive Research, point out that the industry often hails as revolutionary technologies that later turn out to be less important than predicted. Ethanol and biofuels have previously been at the top of an industry chart that he calls the “hype cycle”.

“Automated cars are at the top of the chart right now,” Mr McAlinden says.

The light blue GoRide vans that flit around Ford’s technical centre illuminate the leading carmakers’ response to one of the biggest challenges.

Ford and GM are experimenting with public transport services partly as a hedge against the gradual, long-term decline in the proportion of Americans owning motor vehicles, reflected in recent car sales figures. Even after strong recovery in recent years, the 17.33m vehicle sales in 2015 are still short of the record of 17.35m sales in 2000. The US population expanded 13 per cent over the intervening 15 years.

The decline in car use is generally attributed to factors such as the repopulation of the big US cities, where public transport is better, and lower earning power for young adults.

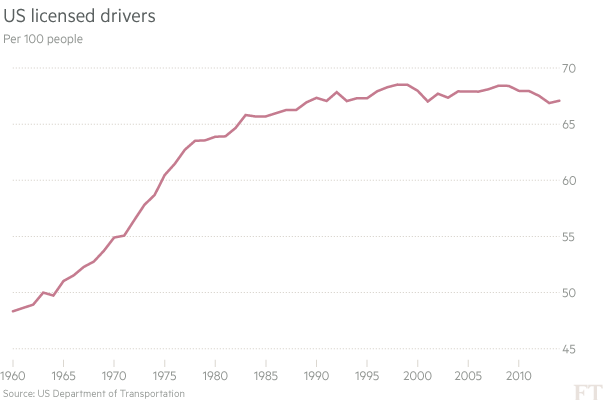

Mark Wakefield, head of automotive for AlixPartners, the leadership consultancy, says there would have been 12m more vehicles on US roads if the proportion of people with driving licences had been the same in 2014 as in 2000. Demand has not received the expected boost from the millennial generation beginning to settle down and have children. “The trend continues and then accelerates,” Mr Wakefield says.

Services similar to GoRide, inspired in part by the success of Uber and other ride-hailing companies, could help carmakers generate revenue even from those who do not own a car. Many mobility experiments revolve around smartphones, which some carmakers blame for stealing young customers’ attention and much of their spending power. Both big US automakers are contemplating launching services similar to GoRide to the general public.

Such investments have a shorter timeframe than projects involving self-driving cars, Mr Nair says. They also have the potential to offer consumers far cheaper options than car ownership.

“The advantage in these mobility solutions — the reason they’re viable solutions — is they reduce the cost to the consumer of personal miles travelled,” he says.

GM and Ford are working still harder at developing autonomous vehicles for use by ride-hailing services like Uber. According to Mike Abelson, GM’s head of strategy, such services will be among the first customers for whom autonomous vehicles make economic sense. Ride-hailing operators will be able to amortise the extra cost of the autonomous technology over far more journeys than a private owner could. GM in January made a $500m investment in Lyft, a ride-hailing service, to collaborate on developing self-driving taxis.

“One of the reasons ride-sharing is so attractive is it provides an economic framework [for investments in autonomous cars],” Mr Abelson says.

Going electric

Inside the battery lab at GM’s technical centre in Warren, Michigan, William Wallace shows off the power source for the Chevrolet Bolt, a low-cost all-electric vehicle that goes on sale this year. The Bolt battery is more than twice as heavy as the one that powered the first hybrid Volt in 2006. But it can deliver 60 kWh of energy, nearly four times the older battery’s 16 kWh.

As GM’s director of global battery systems, Mr Wallace says GM’s attitudes have transformed just as much as the technology. Before its 2009 bankruptcy and subsequent restructuring, GM was mostly risk-averse and conservative, he says. The company is now investing heavily in the battery lab.

“I see it as an indicator of change in the whole leadership mentality, in the willingness to take risk, attack new markets,” Mr Wallace says.

Yet spending on electric vehicle technology is a different matter for Ford and GM from spending on developing autonomous vehicles and other speculative technologies.

Federal rules introduced in 2012 oblige the carmakers to improve their fleets’ average fuel efficiency from 27.5 miles per US gallon at the start of the period to 54.5 mpg when 2025 model year vehicles come on the market in 2024. Mr Nair says Ford has to offer a wide range of vehicles with a significant contribution from electric power to meet the fuel economy targets.

“That’s why electrification is a different prospect now,” he says.

For some other novel technologies, change is likely to take decades, rather than the five years or so that Ms Barra’s comments typically suggest.

The carmakers’ focus on making deals with ride-sharing companies, for example, reflects not only a desire to secure a potentially critical future market but also concerns about the limitations of the latest autonomous vehicle system.

The shortcomings were pointed out in late June when it emerged that the driver of a Tesla vehicle operating on its “autopilot” semi-autonomous mode had died in May after the technology failed to recognise the danger from a truck crossing its path.

The priority for carmakers, when they invest in more speculative technologies, is simply not to miss out if potential entrants such as Google, which has developed substantial autonomous car expertise, or Apple join the market. “You won’t want to break over time into that market with everybody else well established,” Mr Abelson says.

Some already regret one failure, Mr Wakefield says. No one responded after they first heard of Elon Musk’s plans to sell high-end electric vehicles. Tesla Motors, which he founded, has a market capitalisation of $31.6bn after an $889m net loss for 2015 on $4.05bn sales. The capitalisation is only a little lower than the $45.7bn of GM, which earned $9.7bn in 2015 on revenue of $152bn.

“You can call it a fear,” says Mr Wakefield of what drives the traditional carmakers to invest in speculative new technologies. “But it’s almost a fear of missing out, rather than any existential fear.”

Delayed disruption

Yet a slower-than-expected transformation may be the opposite of bad news. The profitability of the new technologies remains far from certain. Vehicles such as the F-150 and the SUVs, whose sales have revived with the oil price fall, not only produce reliable profits but look relatively invulnerable to change.

“Some of the fundamental drivers of our business in North America — full-size pickups and SUVs — will probably be some of the last segments disrupted by the idea of transportation as a service and new urban mobility concepts,” Mr Abelson says.

Mr Wakefield agrees that change is likely to be gradual. He says he asks clients to imagine how their businesses will look in 10, 20 or 30 years. “A lot of the things that get the most press [attention] are the 30-year model,” he says.

Nevertheless, as the US auto industry prepares for sales to peak, the mixture of technological developments to secure their future and robust, profitable sales of existing technology looks to many in the industry like a healthy balance.

“We think in North America we’re pretty well locked with the traditional vehicle segments,” Mr Abelson says. “At the same time we’re exploring what are new opportunities for the company.”

Comments