Harsh realities of a weakened pound

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

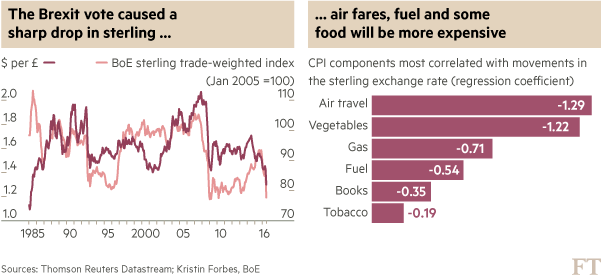

Since Britain voted to leave the EU in June’s referendum, sterling has taken a battering. Against the US dollar, the pound has fallen to a 30-year low, trading on Thursday at $1.29. This was 13 per cent lower than the $1.48 rate that prevailed before it became clear the Leave campaign would win.

Because Brexit has also hit the value of the euro, the composite value of sterling, weighted by Britain’s trading relationships, is down 11.4 per cent to lows not seen since 2011.

But while the moves in sterling’s value are clear, what it means for Britain’s economy is far less certain.

The difficult economics of currency

In recent months economists have made many predictions about the effects of Britain’s exit from the EU, with the vast majority expressing confidence that leaving the bloc will be bad for the UK economy. The same near unanimity and confidence about the effects of sterling’s depreciation will be impossible to find.

Instead of clear advice, economists know the impact on trade flows is ambiguous. In the past, there have also been great variations in the link between a cheaper currency — and more expensive imports — and inflation.

Kristin Forbes, an external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, said last year: “Changes in the exchange rate do not seem to affect different goods and sectors in the most basic ways which one would expect.”

Cause and effect

The main conclusion of Ms Forbes’ research was that the cause of a currency movement is vital in determining its likely effects.

Although she did not make the connection, falling out of a pegged exchange-rate system at a time of artificially high interest rates and high unemployment — as was the case in Britain in 1992 — will have materially different effects than a similar-sized depreciation on the back of a vote to leave the EU with interest rates at 0.5 per cent and full employment.

Dropping out of the European exchange rate mechanism while remaining in the EU in the 1990s encouraged companies to locate themselves in the UK and export into continental Europe.

No one should expect a weaker exchange rate on the back of the new reality of highly uncertain trading links with the EU to have the same galvanising effect, said Richard Barwell of BNP Paribas. “It is surely going to be more difficult for UK companies to attract new long-term customers in overseas markets, irrespective of what they do to prices, if those customers are not sure whether those UK companies are going to be on the wrong side of trade barriers in a few years time.”

Evidence of this behaviour emerged on Thursday in a survey of the German chamber of commerce, obtained by the TUC, which showed a quarter of German companies with operations in the UK planned to cut jobs after the Brexit vote, while one in three planned to invest less in Britain.

Sterling and inflation

A weaker exchange rate will raise certain domestic prices rapidly. Petrol and air fares, where costs are denominated globally in dollars, are obvious examples where prices are already on the rise. The prices of imported fruit and vegetables, tobacco and even books have also been sensitive to sterling in the past.

But the overall relationship between higher import prices and inflation is uncertain. Traditionally, the BoE had a rule of thumb that about 60-90 per cent of the drop in the exchange rate would be felt in higher import prices. An 11 per cent depreciation in sterling’s value, therefore, should add 2-3 per cent to prices over a period of time.

But more recently, the BoE noticed that in the 2007-08 financial crisis, the knock-on effect was much higher. It now thinks that if there is a sudden shock to supply in the UK economy — which would apply if the EU puts up new trade barriers — and a fall in sterling, the inflationary effects will be greater.

In times of a supply shock, Ms Forbes suggests, “UK firms might take advantage of higher import prices to raise domestic prices in order to pay for higher production costs and generate enough cash flow to stay in business”.

That would imply households will be hit harder in the pocket that they might expect from sterling’s current malaise.

Sterling and trade

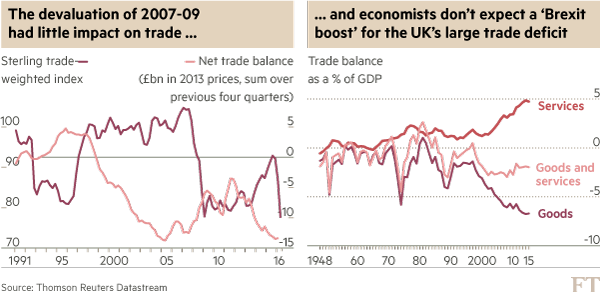

A further problem for those politicians predicting a surge in exports is that the UK’s trade is no longer obviously of the type that responds favourably to a depreciation.

Economics says trade deficits fall if UK consumers switch rapidly to domestic goods and services from their foreign equivalents and if foreigners buy British. But in a study of the 2007-08 depreciation, the BoE found the effects of this were much smaller than in the 1990s because British households kept buying cars made in Germany and other imported goods even though they were more expensive, while the volume of British service exports did not respond rapidly to becoming cheaper in global markets.

Britain’s trade balance did improve but more slowly than in the 1990s and the largest effects came from UK households cutting back on foreign holidays, with some other improvements in exports.

In summary, Brexit has unleashed a different sort of currency depreciation, according to modern economics, one that is less likely to encourage domestic investment for exports, is more likely to raise inflation and will be more painful for hard-pressed families. As David Miles, a former MPC member, told MPs soon after the referendum: “I am not terribly optimistic that, if sterling now stays at the current level, we should expect a marked increase in exports from the UK and a significant reduction in the current account deficit”.

Stephen King, adviser to HSBC, added that if exports were not significantly stimulated, sterling’s fall would have the effect of raising prices faster than wages, thus cutting living standards. “This is when you get into the whole risk of recession, stagnation and income squeezes of one sort or another,” he added.

Comments