Diane Arbus: the magic mirror

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It is impossible to know whether Diane Arbus’s early pictures would carry quite the same sense of foreboding if we knew nothing about her suicide, aged 48, in 1971, or her fascination with people she frequently referred to fondly as “freaks”, the eccentrics, dwarves, transvestites, impersonators, the mentally challenged, who she believed could be metaphors for the human condition, appearing, as she wrote, “somewhere further out than we do”. The idea that her portraits revealed a person’s inner psychology rather than just their outward appearance was widely taken up after her death, when she became the leading representative of a new form of subjective documentary photography, conferring importance on people who had previously been hidden from or rejected by society, legitimising them with her camera.

She was fascinated by difference: the difference between how people looked and how they thought they looked; between the character they had created and the person beneath the disguise. Most of all she admired those who had accepted, even celebrated, their difference and stood before her camera on their own terms. “Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience,” she once said. “Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve passed the test in life. They’re aristocrats.”

Not everybody thought that way. Susan Sontag, in a 1973 essay that would later make up part of her book On Photography, failed to see any humanity at all in Arbus’s pictures. Instead they suggested to her “a naivete which is both coy and sinister”. She wasn’t buying into any empathy argument.

When the posthumous retrospective of Arbus’s work opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in November 1972, it drew the highest attendance ever of any exhibition at MoMA. The monograph of her work, also published that year, has never been out of print. As interest in Arbus grew, it was only fuelled by the restrictions placed upon it by her estate. Anybody wishing to write about Arbus’s life, or reproduce her pictures, had to seek approval from her elder daughter, Doon. The first full biography, by Patricia Bosworth in 1984, was written without the co-operation of Arbus’s family and close friends, and a new biography by Arthur Lubow, published in the US last month, is similarly unauthorised.

At least he had more to go on. In 2003, the touring exhibition Diane Arbus, Revelations did, with the estate’s blessing, just what its title promised: it revealed previously unseen work, even presented a slightly macabre replica of her library rooms and, most surprisingly, disclosed the intimate facts of her life in an annotated chronology complete with family snapshots, drawings, postcards and letters, contact sheets, notebooks, diaries and scribbled lists. At the end — as if to say to the prurient, are you satisfied now? — was her autopsy report, dated July 29 1971: “Final cause of death (9/14/71). Incised wounds of wrists with external haemorrhage. Acute barbiturate poisoning. Suicidal.”

. . .

One of the curators who worked on that exhibition was Jeff Rosenheim, now curator in charge of photographs at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which in 2007 acquired the entire Arbus estate — her negatives, work prints, correspondence and papers. This month, the first fruits of the research into the archive will be revealed in an exhibition of Arbus’s early work, which opens on July 12 at the Met Breuer, the former Whitney Museum building, now the Met’s centre for 20th and 21st-century art.

It covers a seven-year period from 1956, when Arbus, then 33, left the fashion photography partnership she had set up with her husband Allan Arbus, and began to concentrate on her own work. She had been taking pictures since 1941, when her husband made her a present of a camera, and what she knew of the technical side of photography and printing she learnt from him. But 1956 was the year she began to number her contact sheets, and Rosenheim has taken this as a statement of intent.

His selection contains a large number of prints that Arbus made during this period which were stored in boxes in her darkroom and not discovered until several years after her death. Although some of the early images were included in the 1972 MoMA show, none appear in the 1972 monograph, still widely accepted as the definitive collection of her work. All 80 pictures in that book have the same square format, and the earliest date from 1962. But for seven years before that Arbus was using a 35mm camera, with its familiar rectangular format. In 1962 she switched to a Rolleiflex, and it is that square format, pushing the subject to the centre of the frame, that is characteristic of what came to be known as Arbus’s mature work: head on, confrontational, a deliberate exchange between the person behind the camera and the person in front of it.

The early pictures, Rosenheim explains, have always been “presented in a supporting role, as antecedents of what was to follow, rather than achievements in themselves”. Now he is making a claim for their importance. “There are 105 pictures in the show, two-thirds of them have never been published,” he says. And as he explained to Doon Arbus, when he first proposed the show: “[T]he language, the idiom, the experience, the intensity, the haunting quality you find in the late work — it is all there.”

What Arbus would have felt about having them shown in public is a moot point. She worried that nothing was ever good enough, and most artists are leery about people looking through what they see as their immature work. John Szarkowski, then head of photography at MoMA, who in 1967 curated her first group show at the museum (New Documents, with Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand), told Patricia Bosworth that when he’d seen some of Arbus’s early 35mm work, he’d felt, “They weren’t pictures, somehow.” But for Rosenheim, their nascent qualities are what make them so valuable. They show Arbus searching for her own voice, learning how to make her own distinctive pictures, clarifying her vision, daring herself to get more personally involved with her subjects. We see her testing her ability to isolate a subject from his or her surroundings, to single out, for example, a woman whose confident style of dress is undercut by her self-conscious expression of doubt when confronted by this slightly built, crop-headed woman weighed down (as Arbus habitually was) by cameras.

Street photographers were hardly a rarity in New York in the mid-1950s but most of them wanted to be invisible to their subjects. Walker Evans hid his camera lens between the buttons of his coat when he made subway portraits; Helen Levitt used a right-angle lens. “All the other artists of her generation,” Rosenheim says, “Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander — they wanted to work and not be recognised. The true value of documentary was not to influence the world. So they tried really hard to avoid that.”

. . .

Arbus worked very differently. She wanted to be seen. She valued what Rosenheim calls the “singular look of introspection” that she and her camera could evoke. “She felt that she was a magic mirror and there were secrets to be shared and [the fact] that people reacted to her was as interesting as what she was seeing in them,” he says.

At first she didn’t speak to her subjects. “Not at the beginning,” says Rosenheim. “She has asked by her attention to them. [It was a] non-verbal communication. She’s not hiding the camera, she’s revealing it. These are people who have recognised that they are being photographed by her but she seems to be waiting for their moment of recognition. Some give in, and some fight, and some reveal. It’s like each of them is performing their own role in response to hers.

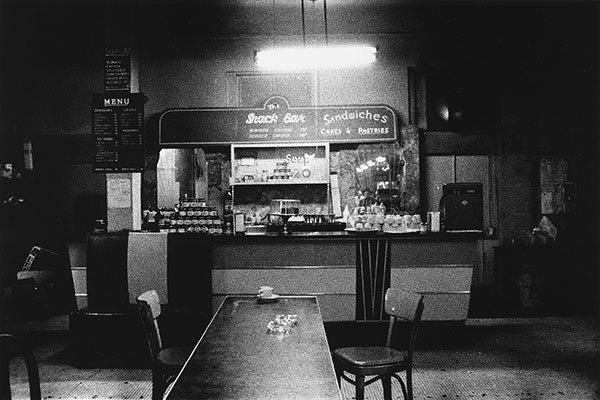

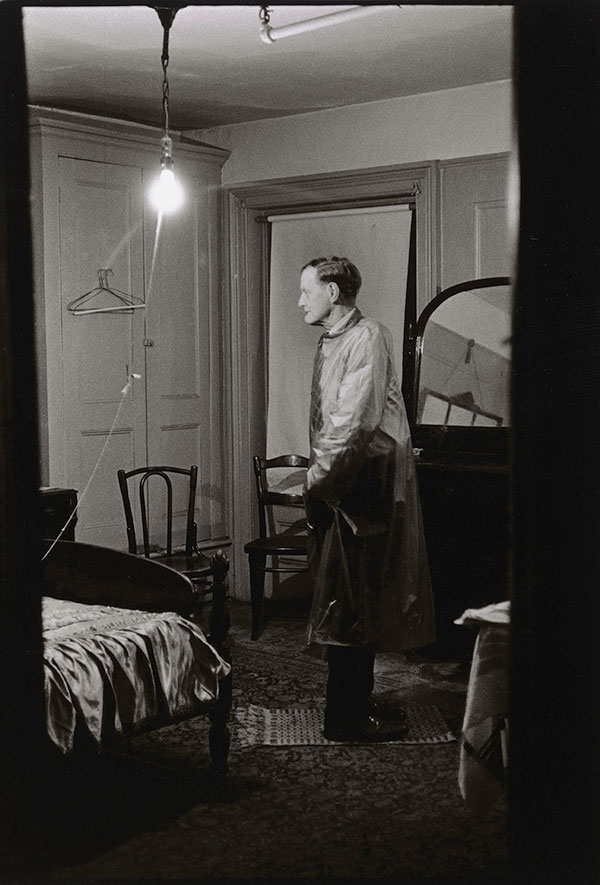

“And then she realises that people she sees on the street she can approach; that they’ve already communicated, they’ve already performed together — this is a kind of performance. And then the world opens up to her, and the next thing she knows she’s in somebody’s hotel room . . ”

He singles out her picture of “The Backwards Man” (1961), a contortionist who has swivelled his body round so his feet face one way and his head faces the other. Arbus described him as “a metaphor for human destiny — walking blind into the future with an eye on the past”.

“But [in this picture] she uses the frame in a really interesting way,” Rosenheim says. “As if she needs you to know that there’s a door and she’s going to take you through that door, and getting from the outside to the inside, that is her art. And when you’re on the inside, you’re in a privileged space. And she can build that privileged space from nothing, and that is magic.”

. . .

Among these early works, several significant themes emerge. One is children. In this period, 1956-62, Arbus had two small daughters to care for. Though Allan Arbus still supported the family, the marriage was beginning to fall apart. On the street or in Central Park, Arbus would have Amy, born in 1954, with her in a pushchair, while Doon, born in 1945, was in school. Children were the first to “get” Arbus, Rosenheim says. “She understood their world and they seem to have become a measure for her, of seeing and being seen. Somehow even the youngest kids understood that in her presence there is an electric communication.” She was particularly drawn to children on the brink of adolescence, a reflection, maybe, of her own closeted, privileged childhood role as the “princess” of Russek’s — the department store founded by her grandfather — which she seems to have spent a lifetime getting away from.

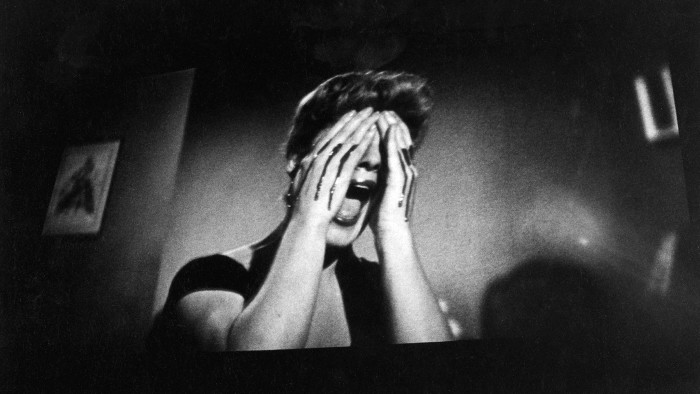

Another subject was the cinema. Arbus was one of the first photographers to use the cinema screen as a subject, isolating moments of high melodrama and passion. “Really [she was] the first person to work off the screen,” Rosenheim says. “They’re film noir and horror movies and people are constantly being strangled and killed.” The movie pictures were among the pictures Arbus showed to Harold Hayes, an editor at Esquire, the first magazine to publish her work. “She would have gone into the cinema to shoot the same scenes over and over again,” Rosenheim says, “because it’s not like you can freeze-frame it.” She even took the bus to New Jersey to photograph a drive-in movie screen at night.

And then there were the freaks themselves. “Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot,” Arbus said. “It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me . . . They made me feel a mixture of shame and awe.” In the summer of 1959, while her daughters were away at camp and with relatives, she travelled outside the city to photograph small-town circuses. She went to Coney Island side-shows and discovered Hubert’s Freak Museum on 42nd Street. Hezekiah Trambles, or “Congo the Jungle Creep”, and Andrew Ratoucheff, a Russian midget actor who did a Marilyn Monroe impersonation, were among the portraits that appeared in a special New York issue of Esquire in July 1960. The following year, Harper’s Bazaar published a portfolio of eccentrics, for which Arbus also wrote the text (her style is as idiosyncratic and distinctive as her pictures). The editor of the magazine refused, however, to publish one of her pictures: Miss Stormé de Laverie, “The Lady Who Appears to Be a Gentleman”, because, according to Patricia Bosworth, it was considered “too disconcerting for Bazaar readers”. Today it would be commonplace, and surely even Susan Sontag wouldn’t begrudge the idea that Arbus was one of the people who had helped make this possible.

“People knew,” Rosenheim says. “People revealed things to her that they would not reveal to their families, to their lovers, to themselves, under normal conditions. [But] they felt like they could share some secret with her. It is non-verbal communication and yet is visualised.

“How do we become the people we want to be? How do we overcome our genetics and our gender, how do we transform ourselves? How do children become adolescents and adolescents become adults? How do adults become parents, how do children distinguish themselves? These are essential questions throughout her work.”

‘Diane Arbus: In the Beginning’ is at the Met Breuer, 945 Madison Avenue, NY 10021, July 12- November 27. The catalogue is published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press, $50 in the US and £35 in the UK; metmuseum.org; yalebooks.co.uk

Photographs: The Estate of Diane Arbus

Comments