Leicester — the city that made the football club

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Riaz Khan was a teenage football fan in Leicester, he became a “casual”. “Casuals”, in 1980s jargon, were youths in trendy designer labels who went to matches “looking for a little scrap” (or fight), he explains. This was the heyday of British football hooliganism, though Khan distinguishes casuals from hooligans, whom he calls “mindless thugs”. For him and his friends, he says, “It was a great day out, something to look forward to in our mundane, boring lives.”

But Khan is Asian. Almost all Leicester casuals — like almost all football spectators in Britain then — were white. “It was very difficult at first,” admits Khan, now a big, bald, capaciously bearded 50-year-old English teacher. Drinking mint tea in the Chaiiwala café in what he describes as a “Slovakian-Asian” neighbourhood of Leicester, he recalls: “Some people wouldn’t talk to you, they’d make snidey remarks: ‘What are all these Pakis doing here?’”

How did his parents view his hobby? “They hated it. They wanted me to be a doctor.” But Khan stuck it out, for the camaraderie and the Italian clothes. Eventually the “firm” of casuals he belonged to — known as the “Leicester Baby Squad” — included about 20 Asians, more than any rival club they encountered.

Tens of thousands of Leicester fans like Khan (author of Khan: Memoirs of an Asian Football Casual) are today watching their team improbably closing in on the English Premier League title. Founded by some members of a Bible class in a garden shed in 1884 and nicknamed “the Foxes” after the county’s foxhunting tradition, Leicester City have never been English champions. Their best performance before this season was in 1929, when they finished second in the Football League.

Leicester City started this season as 5,000-1 outsiders. Yet with just six games left to play, the Foxes are now top of the table, seven points ahead of second-placed Tottenham.

The club’s home town, 100 miles north of London, is unused to the spotlight. There is only one remarkable thing about Leicester: its demographics. This is England’s most racially diverse big city outside London. Only about half of its 330,000 inhabitants described themselves as “white British” in the last census, in 2011. The many ethnic groups — including Asian, British Asian, Caribbean, African and mixed race — get on so well that policy wonks sometimes talk of a “Leicester model”. In a Europe reeling from terrorist attacks, that’s a cheering notion. The story of Leicester and its ascendant football club reveals something about the city’s model — but also about its limits.

Spending time in Leicester, even during its first ever footballing golden age, is pleasant but underwhelming. The city is modestly prosperous. Its architecture ranges from the forgettable to 1960s brutalism. One of the jokes in Sue Townsend’s fictional diaries of unglamorous teenager Adrian Mole is that he lives here, in Townsend’s unglamorous home town. The local conversational style is polite and undramatic, and nobody I spoke to pretended to have an explanation for the team’s success. Clearly it must have something to do with shrewd coaching, conditioning and the scouting of excellent, underrated players such as Riyad Mahrez, Jamie Vardy and N’Golo Kanté. Luck (whisper it) has helped too. But rational factors alone only explain so much. Some locals think that journeyman coach Claudio Ranieri has suddenly, aged 64, become a genius. Others credit Richard III, killed in battle near here in 1485. In 2012, Leicester University archaeologists dug up his remains under a car park. In March 2015 he was ceremonially reburied. Suddenly City — then facing relegation from the Premier League — couldn’t stop winning.

Though Leicester are still winning (usually by 1-0), the city isn’t blowing its own trumpet: in two days of walking the streets here, I saw exactly zero people going about their daily business wearing blue Leicester City shirts or scarves. You’d almost think Leicester were still in League One, the third tier of English football, as they were seven years ago. Only on the five-a-side pitches at St Margaret’s Pastures one cold evening did I spot Leicester tops: of the dozens of local men playing enthusiastic bad football, nearly 10 per cent were wearing them. Had Leicester City’s success got more locals playing? “No!” chirped the woman who runs the sports centre. “Same as always.”

If Newcastle United were topping the league with weeks to go, half the city would be wearing the team’s black and white. But Leicester’s distinctive colours aren’t footballing ones. Rather, they are the black, white and brown of the inhabitants’ faces. Leicester recently became one of three English provincial cities — including smaller Slough and Luton — where no ethnic group is in the majority, according to researchers at Manchester University. The city’s first postwar immigrants came in sprinklings from everywhere: Poles, Ukrainians, West Indians, Punjabis, and Pakistanis like Riaz Khan’s father, a sailor who jumped ship in Britain in 1958 to give his family a better life. Then, in the 1960s and 1970s, Indians from Africa arrived. “I lived on a 50-acre farm with nearly two dozen servants,” Suleman Nagdi, a Muslim from Rhodesia, recalls. “Suddenly I find myself in a two-up, two-down here.”

But most of the Indian newcomers were Gujarati from east Africa. Surinder Sharma arrived as a boy from Nairobi in 1965. His family moved into a terraced house with a toilet in the garden. Two years later, they bought their own house. Sharma became a lifelong Leicester City fan, and a senior civil servant, specialising in diversity.

He recalls that when Uganda’s dictator Idi Amin expelled the country’s Asians in 1972, Leicester City Council placed an announcement in the Ugandan Argus newspaper urging Asians not to come to Leicester, warning that social and health services were “already stretched to the limit” and that schools were full. About 20,000 — a quarter of all Ugandan Asians — came anyway. They became one of Britain’s most successful immigrant groups. They already spoke English, many were entrepreneurs and, as “twice immigrants”, they were expert adaptors. Simon Woolley, a Leicester man of Caribbean origin who runs the nationwide campaigning group Operation Black Vote, says: “There were tales of Asian families coming to Leicester penniless and within two or three years they were millionaires.”

Most east African Asians had grown up with cricket, not football. Those who did go to watch Leicester City risked being rebuffed. City, for most of its history, has been a white working-class institution. (The club refused to speak to me for this article.)

“I started going to the old Filbert Street [stadium] in the mid-1960s,” says Sharma. “The thing that stopped me going was the rise of skinheads in the mid-1970s. I remember Manchester United fans spitting on our fans.”

Opposing supporters would chant at white Leicester fans, “You live in a Little India” — a line that was meant and understood as an insult. Some Leicester fans themselves sang the racist songs that were common in English football until the 1990s.

When I asked Woolley whether he felt comfortable in the stadium as a black teenager in the 1970s, he replied, “No, but I went. I was particularly scared when away fans such as Leeds United would come. There were a number of times when I felt we were running for our lives. There was racism on the terraces, including from the home fans. As an 11-year-old you just felt: ‘Well, that’s what football fans do.’” Not just football fans: in 1976, the National Front won 18 per cent of the vote in Leicester.

Some non-white locals, feeling unwanted at their home town club, began supporting more glamorous teams elsewhere, while often retaining a soft spot for Leicester City. (A dirty secret of British fandom is that many fans support multiple clubs.)

Even today, in a kids’ kickaround in a park in the mostly Muslim Highfields neighbourhood, I saw Chelsea and Manchester United shirts but no Leicester ones. This isn’t entirely an ethnic issue. Arlo White, lead announcer on the Premier League for NBC TV in the US, and a Leicester native, sighs: “One of Leicester’s main issues over the years has been attracting fans, whatever the ethnicity.”

The club arguably isn’t even Leicester’s main sporting institution. John Williams, sociologist of football at Leicester University, notes: “Leicester is a two-club rugby and football city.” A short walk from City’s King Power Stadium is Welford Road, where the Leicester Tigers draw the biggest crowds in English premiership rugby. Leicester also has top-level basketball and cricket teams. Consequently, the football club struggled to acquire a strong identity. “Leicester City has an unrequited enmity with its local rivals,” says Williams. “Leicester’s real rival is Nottingham Forest. But Forest’s real rival is Derby County. That’s part of Leicester’s problem: it’s ignored by its rivals.”

The town itself has been ignored too. “We’ve had a world snooker champion, the winner of [TV programme] The X Factor, [the pop balladeer] Engelbert Humperdinck. But really the city has lived in the shadow of Birmingham, and more locally Nottingham,” White says. “People can’t really place you: people from the south think you are from the north, people from the north think you are from the south.” Khan agrees: “There is no cultural identity here, to be honest with you. We have not seen this projection of, ‘We are proud of being Leicester.’” The writer JB Priestley decades ago felt that the city seemed to “lack character”.

This weak local identity benefited non-white newcomers, says Williams: there was no unified Leicester culture to reject them. Dilwar Hussain, who runs a group called “New Horizons in British Islam” and lives in Leicester, believes that part of the city’s success is that “it’s a very diverse form of diversity”, with so many different ethnic groups. Here there isn’t a white population facing off against an entirely Pakistani-origin population, as in certain northern cities. Rather, the local establishment admitted Asians to the point where many of them became the local establishment. There are Asian pillars of the community, like Nagdi, an MBE whose many titles include deputy lieutenant of the county. Asian festivals mark the local calendar: Leicester’s Hindu and Sikh Diwali celebrations are said to be the biggest outside India.

Leicester’s workplaces are very mixed. The council began aggressively hiring Asians in the 1980s, according to Asian Leicester, an illustrated history of the city by John Martin and Gurharpal Singh. Narborough Road, whose shopkeepers are from at least 22 nationalities ranging from Polish to Afghan, was recently named Britain’s most multicultural street by researchers from the London School of Economics. The shopkeepers copy each others’ methods, and barter among themselves: an immigrant hairdresser might trade a haircut for help filling in an English form, the LSE’s Suzanne Hall told the Leicester Mercury newspaper.

“I think Leicester is such a wonderful place; it’s just unique,” says Khan. “You can always get a job here, no matter what the colour of your skin. People don’t get marginalised, they don’t get radicalised like in Luton.”

Certainly, overt ethnic conflict is rare here (though tensions simmer between different non-white groups). In 2011, when riots hit other English cities, Leicester’s few outbreaks of disorder were “pathetic, a handful of people”, says Khan. Once, after a rabbi was taunted by Muslim kids in a Leicester street, an imam walked through the neighbourhood with him to show support.

But going around the city, you realise that Leicester is less mixed than it seems. The city’s workplaces, shopping districts and even pubs feature people of all colours but most of those out on the street are with someone of their own ethnicity. Khan says: “We don’t live, as such, together. We live side by side.” Hussain adds: “The risk is that the getting along may be quite superficial.”

While the neighbourhood around Leicester University is quite mixed, for instance, walk a quarter of a mile into Highfields and almost everyone looks Asian. The change is “like a light switch”, marvels Williams. Most schools are therefore somewhat segregated. “Birds of a feather will flock together,” shrugs Nagdi. Often it’s just for practical reasons, he adds: “Father and mother go to work, and grandpa and grandma live two doors down, and that’s good for childcare.”

The football club’s fanbase is still largely white British. About 10 years ago, Williams — founder of the Foxes Against Racism group — carried out a survey that showed that only 7 per cent of the club’s home crowd came from ethnic minorities; the figure for the Leicester Tigers was about 1 per cent. He estimates that City’s proportion has since risen to about 10 per cent. That’s more than most English clubs (Williams thinks Arsenal has the Premier League’s most ethnically diverse fanbase) but it’s low for a city that’s half non-white.

Williams accuses the club of having been slow to put pictures of Asian fans in the merchandise catalogue, or to encourage the sale of Asian food at the ground, or do anything to acknowledge that it plays in an ethnically plural city.

True, like almost all English clubs, City has made progress. Foxes fan Narved Plaha says that some of his fellow Sikh supporters now go to the King Power Stadium wearing turbans. As a teenager he wore a bandanna and cap so as not to stand out. Khan says he’s now one of many Asian dads who take their kids to matches.

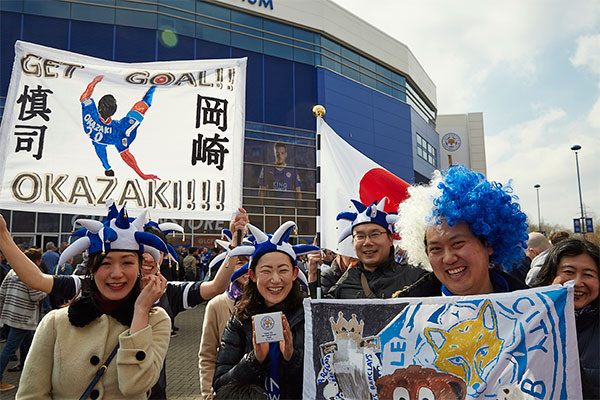

Williams thinks the club’s move in 2002 from central Filbert Street to the King Power Stadium made that easier. The new ground is a rather charmless construction on a commercial estate on the city’s outskirts. But Williams explains: “It’s no longer that forbidding white working-class space. The new stadium is a neutral space.” And Leicester City itself has ceased to be a British white working-class institution. Bought by the Thai duty-free magnate Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha in 2010, the club play in the commercially savvy and global Premier League, and are attracting new audiences: women, Chinese tourists, Singaporean students and more.

But perhaps the biggest Asian absence at Leicester — as at almost all English clubs — is on the playing and coaching staff. Why have so few British Asians become professional footballers? Kirk Master is a half-Asian, half-Irish Leicester city councillor with personal experience of the matter. He was a youth trainee at West Bromwich Albion but never turned pro. British football clubs, he explains, have historically been run by white working-class players and coaches who imposed their way of doing things. He says, “If you don’t know the culture of football — and football does have a culture — how do you start? If you don’t fit into that world, or you don’t know that world exists, you are already on the outside.” For instance, he points out, alcohol used to be so taken for granted in the English game that the man of the match was traditionally awarded a bottle of champagne. After Yaya Touré, a star Muslim player at Manchester City, refused to accept his bottle, the Premier League began offering an alternative rosewater and pomegranate drink.

Even now, incomprehension persists between Asian families and British football clubs. Master asks, “Would an Asian parent understand that they would be expected to take their son to three, maybe four training sessions a week? The dietary needs, the fitness needs, the level of support that the young person requires? They are not able to understand that world well. And I don’t think it’s been presented to them. But clubs are getting better. Leicester City is getting better at that. If I was playing now with today’s culture around Asians in football, I would probably have made it as a pro.”

British Asian female players have it even harder. Annie Zaidi, a Muslim woman who coaches Leicester City’s under-11 girls’ team, says there is only one south Asian girl in the club’s youth academy. “A lot of south Asian, Muslim girls play indoors because it’s more culturally accepted,” she says. “They don’t want to become good, or have the knowledge to become good.”

. . .

When I told foreign friends about my assignment, they asked where Leicester was. The French mispronounce its name as “Layster”, and Americans as “Lie-chester”, instead of “Lester”. But now Leicester City’s run for the title is starting to give the town an identity, at home and worldwide. Nagdi muses, “A city in the Midlands, not particularly large, and suddenly it’s on the international map.”

Riaz Ravat of the interfaith St Philip’s Centre says, “Journalists are descending on Leicester asking, ‘What is this city, in the middle of the UK?’ The Midlands often gets ignored, or the Midlands means Birmingham.” Master says the club’s success is “making Leicester a sellable brand across the globe”. Perhaps not coincidentally, the council will soon appoint a director of tourism and trade.

In Leicester itself, everyone has gone football-mad, at least by local standards. Zaidi says she drove through town during the recent Leicester-Newcastle game, and “all the streets were quiet. You could see people going to each other’s houses, and watching football. It’s one of them magical places. I think my journey as a coach parallels the Leicester journey, because a lot of people said I couldn’t. Now I’m doing my international [coaching] licence. Whatever people say to you, just go out and do it.” Her dream is to succeed Arsène Wenger as manager of her beloved Arsenal.

Leicester’s success seems to be helping to nudge local integration along. Even young imams have been spotted wearing Leicester City shirts and scarves. Helpfully, the team’s black, brown and white heroes speak to all the local demographics. Khan says he sees Mahrez at his local mosque most Fridays. “That’s in a Somali area. And the rumours about [his signing for] Arsenal and Barcelona are not true, by the way. Mahrez and Kanté go to a local hairdresser, £3.50 for a haircut, nothing fancy.”

Leicester folk of all ethnicities are now united in stomach-churning anxiety. As White puts it: “The fear is that it’s going to go wrong, because it’s Leicester City.” But if the team doesn’t blow it, this quiet city will go noisily crazy. Locals know what that looks like. It was the same here in 2011 when India won the cricket world cup.

Photographs: Getty; Brian Doherty; aerialphotography.org.uk

Comments