Unpaid bills add to China debt problems as receivables mount

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Times have changed for Yu Xingzhi since China’s economic boom years. Despite the slowing economy, sales at Shanghai Caison Color Material Chemical are holding up. The trouble is, her customers — garment manufacturers and packaging producers buying her dyes and inks — are taking more time to pay for what they buy.

“Receivables are the unavoidable problem for traditional manufacturers. If you don’t accept receivables, you have no business. It’s standard industry practice, even though no one likes it,” says Ms Yu, the dyemaker’s general manager.

It is a vicious circle and one threatening the health of the economy. Ever longer delays in bills being paid are creating a chain of squeezed cash flow and debt that runs from large state-owned enterprises through to smaller suppliers and even employees struggling to pay their own bills.

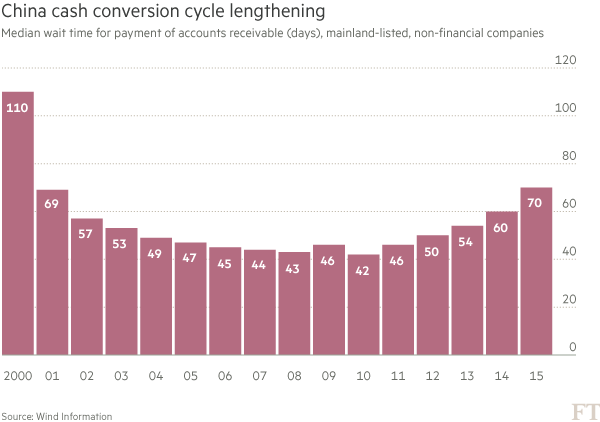

Listed companies had to wait a median 70 days to receive payment last year, the longest delay in 14 years, as cash flows tightened amid slack final demand. That compares with a median 60 days in 2014 and 46 days in 2011, according to Wind Information, a Chinese financial database.

Ms Yu says that an increasing share of customers now insist on paying with a bankers’ acceptance rather than cash. Similar to a postdated cheque, bankers acceptances are a kind of IOU from a company and its bank. Ms Xu says that a few years ago, 5 to 10 per cent of her sales were paid this way, but that has now risen to 20 to 30 per cent. Most cannot be cashed for 90 or 180 days.

Nor does the problem end with Ms Yu. “We have no choice but to pass the delays upstream [to our suppliers],” she says.

China’s supply chain is more dense than in Europe or the US, and often concentrated in localities — meaning bills that go unpaid for months have a knock-on effect that can quickly rip through entire industrial ecosystems.

Thus when Shenzhen Eycom Technology Co, which makes hardware and software for mobile phones, held up payments two of its Shenzhen-listed vendors were forced to warn investors in stock exchange filings. In Nanchang city, in China’s southern Jiangxi province, a small manufacturer of medical-grade plastic blamed late payments from customers for its inability to pay Rmb1.1m in salaries to more than 120 employees last September, prompting a fine from the local labour bureau, according to local media.

The woes of the Shenzhen group, which operates in a notoriously competitive and low-margin industry, illustrate what economists say is the crux of the problem: weak final demand, especially in low-end manufacturing sectors wracked with overcapacity. Companies must whittle down inventories before they have enough cash to pay suppliers.

But the build-up of receivables also reflects bottlenecks in the financial system. China’s central bank has eased monetary policy substantially since late 2014. But looser money often fails to reach smaller, privately owned businesses that struggle most in paying their bills on time.

“It looks like liquidity is very ample, but a lot of that is being used to help the real estate sector refinance. It's not circulating widely through the economy,” says Shao Yu, economist at Oriental Securities in Shanghai.

The banks, however, sniff opportunity in the rising stock of receivables: both financing and securitising payments. Financing is dominated by the Big 4 state-owned “bad banks”, which once exclusively purchased non-performing loans from commercial banks but have now diversified into other distressed assets.

At China Huarong Asset Management, the country’s biggest bad bank, nearly two-thirds of newly acquired assets, or Rmb147bn, were from non-banks in 2015. Non-bank assets were “mainly” corporate receivables, Huarong said in its annual report. Following years of pilot projects, in February, eight government agencies led by the People's Bank of China issued policy guidelines that pledged to “accelerate securitisation of receivables” in order to “revitalise the stock of industrial assets”.

Many Hong Kong exporters have adopted a 30-40-30 structure to keep cash flows running, whereby customers make partial payment before, during and after shipment.

Willy Lin, managing director of Hong Kong-based Milo’s Knitwear — which exports upmarket China-made clothes to Europe — says he and other Hong Kong exporters are “playing safe” with payment terms. He typically uses a 30-40-30 structure in which customers make partial payment before, during and after shipment.

Mr Lin says that high-end manufacturers, whose customers cannot easily switch to a competitor, have more bargaining power, but that he is aware many smaller Chinese manufacturers face increasing difficulty.

“The problem is quite common in mainland private enterprises because many of the companies rely on guanxi [connections] and nepotism to make a business deal. A deal usually comes from friend of a friend or someone’s relatives,” says Mr Lin.

Additional reporting by Ma Nan and Gloria Cheung

Twitter: @gabewildau

Comments