Why employers’ assumptions about the over-50s are wrong

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Stephen Sheppard became operations director of a company in October 2015, he was confronted with a problem. The 54-year-old had little idea how to operate the resource management software that ran the business.

His employer, London-based Olive Services, a facilities and catering contract management company, was happy for him to learn on the job.

“I was unfamiliar with the system and I haven’t totally mastered it yet,” he says.

But he adds that keeping up with the latest business software is essential for him. Despite having no formal technical education, he has been able to stay up-to-date with computer systems through a combination of his own efforts and support from his employers. It is a joint responsibility, he says.

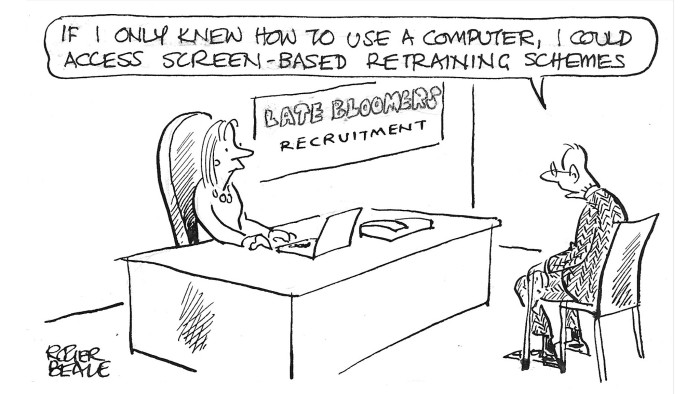

Peter Knight, chief executive of Forties People, a London-based recruitment agency specialising in older workers, says the first challenges this group often faces are grappling with online application forms or how to use software to make their CVs look smart.

His agency provides screen-based training that applicants can use from home to acquire skills and take tests to demonstrate their expertise to potential employers.

Joe Coughlin, director of the Boston-based MIT AgeLab in the US, carries out research on how older people interact with society. He says that, in the future, workers will need to invest in their education and society will have to support older people if they want to stay employed.

“This is a profound societal transformation,” he says. “Technology is causing a second industrial revolution and has huge potential for productivity and the engagement of older people in the workplace.”

In terms of their professional knowledge, younger generations will age faster than their parents and grandparents, Mr Coughlin says. “Technology is moving so fast that today’s 35-year-old is probably as antiquated as the 55-year-old was 20 years ago.”

The new normal life expectancy will be 100. Working life will be 60 years. “Few of us enjoy what we do so much that we want to do it for six decades, so we are going to want multiple careers. A college education no longer lasts for decades of work,” says Mr Coughlin.

Workers will need help to learn technological skills for professions not yet invented, he adds. “Roles such as data scientist and social media consultant were unheard of 10 years ago.”

Keeping staff up-to-date also benefits organisations. Older workers able to use knowledge management systems can transfer their expertise and experience to others so that it is not lost when they finally walk out of the door.

Technology’s ability to keep people employed extends beyond white-collar workers to those in jobs that are physically demanding or based outside. “By 50, their bodies are beginning to wear out,” says Mr Coughlin.

Already robotics and exoskeletal systems that can help people avoid hurting themselves in tasks such as heavy lifting are beginning to appear on assembly lines and construction sites.

Employers need to forget the stereotypical view that after a certain age people are either uncompetitive and unwilling to learn, or that people are more technically savvy at some ages than others. “They need to look at value not birthdays,” says Mr Coughlin.

Older people often apply themselves to learning new systems more diligently than younger workers, adds Mr Knight. “It may take slightly longer, but once they have acquired a skill, they are less likely to forget it.”

And, while younger people are able to use technology more intuitively, mature workers tend to be more focused and have better communications skills, he says.

“They talk to people or pick up the phone, whereas millennials tend to keep their heads down and communicate electronically.”

Lesley Uren, a talent management expert with PA Consulting, agrees that older people are often better at important skills such as listening and empathising.

“As communication becomes more virtual, we need to be much more aware of our impact on others.”

Older people must stop fearing technology, says Ms Uren. “Rather than clutch at the idea that use of social media might be declining, they should get on top of such technologies because they are here to stay.”

Comments