Philip Green on building a retail empire: ‘I don’t regret anything I haven’t done’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

From a terrace six floors above London’s Oxford Street, Sir Philip Green is surveying his domain. If the retail magnate were to look down over the shiny black marble balustrade, he would see London’s prime shopping district is even busier than usual. It is sunny, and a Tube strike has driven commuters on to the streets.

Yet Green prefers to stay in the air-conditioned quiet of his black, cream and chrome-decorated head office rather than descend to join the shoppers. Oddly, for a man who has cultivated a streetwise image, he fears he would be mobbed by the public if he took the short stroll west to Oxford Circus to visit the flagship stores of Topshop and Topman, his family’s fast-fashion brands.

Green — portly, with grey-white curls slicked back from his balding forehead and stubble peppering his jowls — has the permanent tycoon-tan of a man with his own jet and yacht. He is dressed in the formal attire of a successful entrepreneur — well-cut dark suit and white shirt, top two buttons undone.

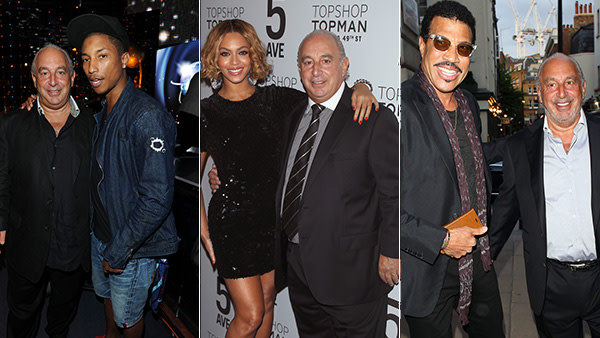

Green claims he neither knows nor cares how much he is worth but The Sunday Times Rich List puts his and his wife Tina’s fortune at £3.5bn. The tabloid newspapers regularly chronicle his connections with models and celebrities, at parties or on his boat. But at 63, he still craves recognition of what he has achieved. In an interview, he constantly throws out his own questions, inviting confirmation of his success.

“Hopefully, as an uneducated, unqualified guy, from 16 years old, [it] hasn’t worked out too bad,” he says in his strong London accent. “I think I’ve backed my judgment. I don’t have disputes with people. Never been in litigation. That’s not bad, is it?” Then later: “If I add up, including Arcadia, over 40 years, I think [I’ve run] plus or minus 5,000 shops. That’s going to give you a bit of experience, isn’t it?”

Arcadia is the vehicle for Topshop, Topman, Dorothy Perkins, Wallis, Evans, Burton and Miss Selfridge, all among Britain’s best-known high-street brands, all ultimately controlled by Tina, a Monaco tax-resident, and other close family. But lately, the man who acquired a retail empire — and twice came close to crowning it with the purchase of Marks and Spencer, the best-known name in British shopkeeping — has started to sell.

In March, Green reluctantly disposed of BHS, formerly British Home Stores, the loss-making clothing and household goods chain whose takeover and revival in the 2000s served notice of his talent as an owner-manager. But the sale price was £1 and the buyers were a virtually unknown group of investors. Outsiders believe if BHS were to go under, it could still hurt Green’s reputation. It would also drag attention back to his family’s offshore tax status, about which he is acutely sensitive, and potentially tarnish any legacy.

Meanwhile, Green still swears by the instinctive sourcing-to-shopfloor skills on which he built his fortune, such as his ability to value instantly any item. But some believe those talents are less valuable in a business whose future will owe less to Oxford Street savvy and more to understanding the online marketplace.

His old antagonist Stuart (now Lord) Rose, who was M&S chief executive when Green launched his second unsuccessful takeover attempt in 2004, says: “He’s more of a yesterday’s man than he is a tomorrow’s man. He’s a classic bricks-and-mortar retailer. Time has caught him up.”

Philip Green’s soft start in life somewhat belies his image as a self-made hard man of retail. He went to the now defunct private Carmel College, known as “the Jewish Eton”, though he did not take to it. Green’s father, who was a small businessman, died when he was 12, which some have used to explain his dysfunctional school career. Matthew Engel, the writer and FT columnist, who was a couple of years above him at Carmel, says Green never fitted in, describing him as “rather cheeky and not very nice”. Certainly his flamboyant career makes him an outlier among other more understated Old Carmelis.

Green left school at 16 with no O-levels. But he had already been working with his entrepreneurial mother Alma in the holidays. “I wasn’t a good school pupil,” says Green. “I was interested in business. I wasn’t going to be a uni player, so [I thought] I’d better go to work: £20 a week, and off we went.”

Green picked up the fundamentals of trade and retail from observing his mother, who owned a portfolio of garages and car showrooms. After an apprenticeship at a footwear wholesaler in his late teens, and backed by a £20,000 loan from his family — a relatively substantial sum at the time — he broke into the clothing business at 21, as a middleman in the early 1970s in Fitzrovia’s bustling rag trade. Derek Lovelock, another retailer who knew Green then, recalls: “There was a group of them that could swoop on any excess stock anywhere, commit, make an instant decision and sell it on.”

Green’s first significant deal was the purchase of ailing fashion chain Jean Jeanie for £65,000 in 1985, which he worked hard to revive. “I used to leave my house at 6.30 in the morning and I would visit 10 shops every Saturday, starting at the furthest shop I’d decided to go to that day, ending up in Oxford Street 12 hours later,” he says.

Within a year he had sold the chain for several million, building his capital and credibility with lenders. But both were dented three years later when Green made his first, and last, foray into the running of publicly listed companies, as chief executive of menswear retail group Amber Day. Green invested his own money, unusually for the boss of a listed company at the time. But he resigned in 1992, under pressure from the board, when profits fell short of expectations. It was a chastening but formative experience, which Green has called “the best thing that ever happened” to him. But when he started to tilt at larger businesses at the end of the decade, the whispering campaign that had helped drive Green from Amber Day meant he was short of supporters in the City of London.

The Green bio1952

Born in Croydon

1968

Leaves Carmel College at 16 with no O-levels

1985

Secures his first big deal with the purchase of Jean Jeanie for £65,000

1990

Marries Tina, whom he had met five years earlier

2000

Abandons his bid for M&S, begun in 1999, and buys BHS for £200m

2002

Buys Arcadia clothing group for £840m

2004

Attempts a second M&S bid

2005

Tina, the legal owner of Arcadia, receives a controversial £1.2bn dividend

2006

Green is knighted

2012

Arcadia partners with US retailer Nordstrom. Leonard Green & Partners take a 25 per cent stake in Topshop

2015

Sells BHS for £1 to little-known investor group

Robin Saunders, then at WestLB, the German regional bank, was one backer. Saunders saw in Green some of the same business genius that she had detected in another maverick she supported, Bernie Ecclestone, who still runs the Formula One motorsport business. Saunders explains that it was hard to raise money for Green’s first bid for Marks and Spencer in 1999. “I couldn’t understand that, because I thought he was brilliant, he was really good at what he does,” she says. But she adds: “We bankers can be sheep and so once ‘PG’ had been able to demonstrate what he was capable of, everybody wanted to bank him.”

Green abandoned that first approach to M&S after a public relations campaign focused media attention on the (lawful) purchase of shares by his wife before he had made public his interest in buying the retail chain. His withdrawal left him free to buy and turn round BHS — then a dowdy but familiar presence in UK retailing — a few months later, again with Saunders’ support.

Riding the BHS success, Green was able to push through an offer for Arcadia in 2002, whose brands remain the centrepiece of the retail group. It was a hallmark Philip Green deal: less than £10m of the £840m paid came from his family and the rest from a consortium of banks. “Arcadia was a typical venture capital deal, but I’m the adventurer and the capitalist,” says Green.

It was the second M&S bid in 2004, though, that cemented the larger-than-life reputation of Green as an aggressive, brash, sometimes unpredictable business personality — in contrast to the dull suits running the listed retail companies. The bid was notable both for the substantial blue-chip backing Green received (from Goldman Sachs, for example, as both adviser and source of finance) and for the bad blood between Green and Rose, who had turned down an earlier offer to work for the entrepreneur before agreeing to lead M&S’s defence.

In the most infamous incident, Green confronted Rose as he was getting out of his car outside M&S headquarters and attacked him verbally. “I opened his door for him and said, ‘I want to talk to you,’” says Green. He then handed his mobile phone to Rose so his wife Tina could weigh in from Monaco. “I admired the guy’s chutzpah,” says Rose now. “What I like about him is that Philip will punch you if he thinks he’s got a reason to punch you but if you punch him back he’s quite able to take the punch.”

In fact, Green came very close to winning M&S. Advisers and insiders say the M&S board was wavering when the retail magnate unexpectedly pulled out, unwilling to increase his offer. “I don’t regret anything I haven’t done,” says Green today. He thinks, with hindsight, that ownership of M&S could have brought him “a whole load of life’s aggravations”.

“I think these very big companies that have got a history are quite difficult to own,” he adds. “I think there is a lot we could have done but I think, at the same time, the distractions of trying to do it is quite difficult.”

. . .

Buying M&S would certainly have focused even greater attention on his family’s tax arrangements, which Green claims owe more to a series of potentially life-changing events in the mid-1990s than to any prescience about future tax advantages.

Green married Tina, who has her own luxury interior design business, in 1990. She was married to businessman Robert Palos when she first met Green in 1985. She told the Daily Mail, in a rare interview in 2005, that her first reaction was that he was “dreadful”: “I remember him asking me who I was. I said I ran a boutique called Harabels and he said, rather dismissively, ‘Well I’ve never heard of it.’ I thought: ‘What an arrogant man.’” They celebrated their silver wedding anniversary quietly last weekend. One person who knows Green well says: “You can’t underestimate Tina. She’s brilliantly capable.”

Five years after they married, however, Green had a series of heart scares that left him with eight stents in his chest, worrying Tina and Green himself. In 1997, the entrepreneur was held up by muggers near his home in St John’s Wood, where the couple and their young children, Chloe and Brandon, were living.

“I walked to the corner and some guy attacked me with a sword,” says Green. “I had had two lots of heart surgery and I thought, ‘Do you know what? Enough.’ I thought, have some time out, maybe it’s a warning. [At] that time I didn’t even know I was going to work again . . . I just made a decision [to move the family out of the UK].”

He took some time off in 1998, partly at Tina’s insistence, but jokes now that “there would have been a murder” if he had had to spend any longer “walking along a beach holding hands”. By the end of the year, he was back forging the deals that created both huge wealth and intense interest in how that wealth was distributed.

In 2005, the banks that had backed the Arcadia bid agreed to issue new loans. That refinancing, combined with Green’s retail nous and cost-cutting abilities, generated a £1.2bn dividend for Tina. As a Monaco resident, she paid no tax in the UK. The following year, Green was awarded a knighthood for services to retailing during Tony Blair’s administration.

The payout, and honour, were criticised at the time but the atmosphere really soured after the financial crisis. In 2010, Green was appointed by the coalition government to advise on efficiency in Whitehall, just as the Lib Dems launched a drive against tax avoidance. The concerns boiled to the surface. His report on Whitehall found “massive wastage” but the focus on his family’s tax affairs led to attacks on Topshop branches by activists.

Green recalls watching the news with friends who were visiting: “[One said]: ‘Isn’t that your shop?’ And there were 80 or 100 police with riot shields surrounding the [Oxford Circus] building . . . Not nice.” He has pointed out that he is himself a UK taxpayer and that Arcadia has over the years paid billions in UK taxes but he still sounds aggrieved that his family is often singled out for avoidance. “It was never done on that basis,” he protests. “It transpired that circumstances evolved. In 1998, we didn’t know anything. We didn’t have a business.”

As for the dividend itself — £1.3bn including the payout to minority shareholders — he believes that it should be recognised as an indication of his business acumen. It was, he points out, one and a half times what was paid for Arcadia only three years earlier, and a far greater multiple of the cash the family originally put up. “It was a big piece of money,” he says with evident pride. “Nobody else has done it.”

. . .

Green’s style is best described as argumentative, to the point of confrontational. His anger is often turned on journalists who criticise him, or advisers who refuse to see his point of view. One person who worked with him recalls seeing bankers driven from his office in tears. People are “petrified” and “intimidated” by Green, says another. Few of those contacted for this article wished to criticise him on the record. But Green — who likes to orchestrate press coverage if he can — arranged for a flood of calls from friends and business partners eager to offer attributable praise.

Jon Sokoloff, managing partner of Leonard Green, the US private equity group, read a lot about Green ahead of the 2012 deal in which the private equity group invested £350m for a 25 per cent stake in Topshop and Topman: “I thought to myself: this is someone I would much rather work with than compete with.”

“The volcanoes erupt frequently,” says Ian Grabiner, Arcadia’s chief executive and owner of a small stake in the business, who has known Green since 1988. “He’s very sensitive but I think that for all people like Philip, insecurity is a factor, because in their minds they have got to continue to be successful . . . There’s a very childish side to Philip that looks for affection.”

Green denies he is an angry man. Some of the same people who have been on the wrong end of his ill-tempered outbursts say he also makes them laugh with his rough sense of humour and expletive-laden criticism of rivals. “If I had a row with you now, by the time I walked to my next meeting, nobody would even know I got upset 10 minutes earlier,” the retailer says. “Because I got teed off with one lot of people [in one meeting], I can’t then take that to the next meeting and get annoyed with them for no reason. I’ve got to turn up in the right frame of mind.”

“One of his talents is that whilst he’s shouting at people, he is still being perfectly logical,” says another person who worked with him. “He doesn’t lose what he wants to say or the thread of his argument. He just makes it a bit louder.”

In 2012, Arcadia partnered with the US retailer Nordstrom to feature Topshop and Topman collections in its department stores. After agreeing the deal, Green insisted on adding lots of denim — a staple of his clothing lines since the 1970s — despite the Nordstrom team’s doubts. “He was very passionate,” Pete Nordstrom, co-president, says, diplomatically. What Green actually said, according to insiders, is: “I’ll put the f***ing denim in. I’ll back it.” He also agreed to cover any markdown if the line did not sell. It sold.

Green keeps up a near-constant conversation with staff, industry contacts, friends, associates and journalists. People who know him say it is his way of gathering intelligence, asserting his relevance and keeping control. He vastly prefers phone or face-to-face contact to email, which he uses only rarely.

“I can get there quicker,” he explains. “If I’m texting with somebody, after the sixth text, I say: ‘Well, phone me. What’s the question? OK, that took eight seconds. Goodbye!’ Or vice versa. So I just think; I want to see people. It depends what it is but, in the main, I think it’s still better to have eye contact and see people. OK: explain that to me, show me, whatever it may be.”

He is no fan of tablets and smartphones, despite their increasing importance to young shoppers. “I don’t allow any machines in my meetings. No calculators, no gadgets. You’ve got to use this,” he says, tapping the side of his well-coiffed head. His two unfashionable Nokia 6310 mobile phones (one for incoming, one for outgoing calls) are never switched off.

Everyone talks about Green’s gift for mental arithmetic, instant assessment of value, fast decision making and simplification of complex business dilemmas. He rarely writes anything down and significant deals are struck on a handshake. “If I say I’m on, I’m on, and if I’m off, I’m off,” says the entrepreneur, who teaches his children the importance of trust. “[If] I look somebody in the eye and say ‘I’m done’, I’m done.”

Challenge his mastery of detail and you will get a rapid lesson in how he became one of the kings of the high street. Bob Wigley, a former Merrill Lynch investment banker, recalls a meeting during the second tumultuous attempt to buy M&S, when, at about 2am, he was rash enough to question his client’s valuation skills: “[Green] said ‘Come with me’ and he took me into the depths of the buying department and he went through every item on the rack: where it came from, how long it would take to sell.”

Another notable attribute — despite his adventurous deals — is Green’s prudence. His advisers say this innate caution was the reason he did not increase his second bid for M&S. (The M&S team still say he lost his nerve.) Sir Tom Hunter, the Scottish multimillionaire who paired up with Green to do deals in the 1990s, says: “Philip was never a big bet-the-ranch sort of guy like Rupert Murdoch who would roll the dice and risk everything on the next deal.”

. . .

The night before the FT’s first interview with Green, the Arcadia boss was the centre of attention at a showy celebration for the Fashion Retail Academy’s 10th anniversary. The academy came into being in 2005, largely as a result of his drive and cussedness, to offer young people a hands-on education in the business.

The Grand Temple of Freemasons’ Hall was packed with students celebrating their graduation. Retail royalty from Britain’s biggest chains, including Marks and Spencer, Next and Tesco — also supporters of the academy — were present. Soul diva Paloma Faith sang; celebrity presenter Vernon Kay played host.

Tony Blair, who as premier gave the academy his blessing in 2005, was an incongruous presence. To the biggest cheer of the night, he described the retail magnate as “the person who thought up a dream and turned the dream into reality”. Addressing the students, Green said retailing was “a fantastic business and full of excitement and there has never been a better time to come into the industry . . . The opportunities are endless.”

For Green, though, the opportunities may be running out. The decision to sell BHS was hugely emotional, not only because of his longstanding ties with the group and its 11,000 staff, but because it represented a missed chance to offload the chain sooner. “He changed his mind every hour before we sold it,” says Ian Grabiner. Chris Harris, another Arcadia executive director, says Green, who rarely dwells on the past, kept pulling out old press cuttings about his investment in BHS while the sale was under discussion.

Arcadia brands still trade through BHS stores and, if BHS failed, the Pensions Regulator could still ask Green to support the BHS retirement scheme. “This one will come back to bite Philip Green,” predicts John Ralfe, an independent pensions adviser.

Last week, BHS secured a loan of about £65m from an investment group to overhaul its stores. Green declines to comment on the pension situation or on BHS’s prospects, which he underpinned by writing off most intra-company loans. But he says ruefully, “I wish I’d have sold it a long, long time back. I should have sold it, but didn’t.”

Ownership of BHS meant he was “spread too thin”, he adds. Now, “we’ve got ourselves in a very nice, clean position, and I think that at my time of life, I don’t want to kill myself. It’s about focus, and I want to focus on what we’ve got.” That means chiefly the future of Topshop and Topman outside the UK, where investment group Leonard Green is backing expansion.

David (now Lord) Alliance, who once ran a textile and apparel empire, says Green is “a great retailer and they don’t make them any more”. Green’s friend Mike Ashley, the brains behind sporting goods retailer Sports Direct, is one who bears comparison. Green, who hosted his 50th birthday party dressed as a Roman emperor, calls Ashley “the Little Emperor” or “Little Emp”. But the reclusive Ashley’s strength is as a merchandiser rather than an all-round merchant, the word frequently applied to Green by admirers.

But Green’s attention to detail is potentially less useful in the new online world. Retailing has changed since 2007, the high point of Topshop’s popularity, when shoppers queued for a glimpse of Green and his personal friend Kate Moss at its flagship Oxford Street store, eager to buy from the supermodel’s new line of affordable fashion. The retailer came to the FT interview from a morning reviewing the online competition with his team. But he is still more comfortable with a walk round the sales floor. The day after the awards event, when Green shows off a selfie of him and Ciara, the singer-celebrity who is the US face of Topshop, it is on a sheet of A4, printed out by his staff.

Richard Hyman, veteran analyst and founder of Verdict, the retail research group, says: “Arcadia’s philosophy is very much rooted in where retail has come from: trading for cash, negotiating better terms, and looking at a product and saying ‘What do you pay for that?’ Whereas the question really is ‘Is that what she [the customer] wants?’”

Green is adamant that his established skills remain valid. “This fallacy that people think the high street is not going to be here in 10 years’ time: this is evolution, not revolution. People want to go shopping,” he says. “You’ve got to understand the product, the buying, how you make it, all the other things, whether you’re selling online or physically, all the other competencies still remain.”

One question is why Green does not switch focus altogether. “If I was him, I would [now] enjoy my time, and enjoy what I’ve got and enjoy my family, but Philip Green isn’t that person,” says Bob Wigley, the former investment banker.

Green does reap the benefits of success. When in the UK, he stays in London’s luxury Dorchester hotel. He shuttles to Monaco and back in his Gulfstream G550 private jet. His lavish parties have entered billionaire lore: the “Roman” 50th birthday in Cyprus; the 60th, in Mexico, with bespoke “PG60” branding; his son Brandon’s bar mitzvah in 2005, featuring music from Beyoncé and a giant pop-up synagogue at a French hotel. And he takes time away from the business, including a six-week stretch this summer holidaying with his family on his 63-metre superyacht Lionheart, where he was joined by guests such as Lionel Richie, another celebrity friend. For his birthday this year, Tina commissioned a cake featuring the Arcadia boss relaxing in bed, upper torso disconcertingly exposed, with “his greatest love”, Louie, a terrier, and one of his two phones visible on the bedside table.

But what happens after Arcadia is barely even open for discussion. Green’s mother Alma died on January 5. “She was 96. I’ve got plenty of time,” he responds, gruffly, when asked whether it had prompted him to think about handing the business on.

Tina’s son from her first marriage, Brett Palos, is a director of Arcadia’s holding company as well as an investor in his own right. But while Chloe, the Greens’ daughter, has launched her own brand of shoes and accessories, and Brandon is training at the group, the entrepreneur wonders whether they have the extra commitment they would need to succeed in the business. “You come in, who are you? ‘I’m the boss’s son or the boss’s daughter.’ I don’t think that’s a good tag. I think you’ve got to earn that . . . Good doesn’t do it. If you’re the boss’s kids, you’ve got to be way past good. And they’re both very smart, but you’ve got to dedicate yourself to this stuff, it doesn’t happen on its own.”

People who know Green believe he would never be happy being a hands-off owner. If he does exit, it will be “with a bang”, says one Arcadia insider, perhaps even selling everything at a stroke. “It would not surprise me if in six months’ time he sold Topshop and got out of retail,” agrees Stuart Rose. The repercussions from BHS, should it fail to make its way outside the Arcadia umbrella, could be a trigger.

Green’s lack of long-term strategic vision means a quick decision would not be out of character. “I have never, ever had a plan,” he says. “When each of the things I’ve done turned up, it happened on the moment, and I’ve always been able to perform pretty quickly.”

By the same token, Green could surprise followers with another big purchase. At a second meeting with the FT earlier this month, he was interested by a report that Christo Wiese, a South African retail billionaire 10 years Green’s senior, was interested in opportunities in the troubled UK supermarket sector. “I’ve got the maximum flexibility,” said Green. “I’m not under any pressure either way. Something turns up — something I haven’t even thought about — who knows? That’s the beauty of it . . . Who knows what tomorrow brings?”

In a way that the hired hands running other retailers are not, Philip Green is Arcadia, bound up with its success, wounded by its failures. If something went wrong, with his health or his business, it is possible to imagine Green calling it a day, as he nearly did in 1998, and settling down with Tina and the dog in Monaco. But as the last merchant says, when asked if he could have chosen to apply the same energy to another business: “If I had wheels, I’d be a car. If: it’s a big word, isn’t it? I can’t deal in if.”

Andrew Hill is the FT’s management editor; Andrea Felsted is senior retail correspondent

Portrait by Benjamin McMahon

Photographs: Rex; Getty; PA images; Corbis

Comments