How battle over Brexit crosses traditional party lines

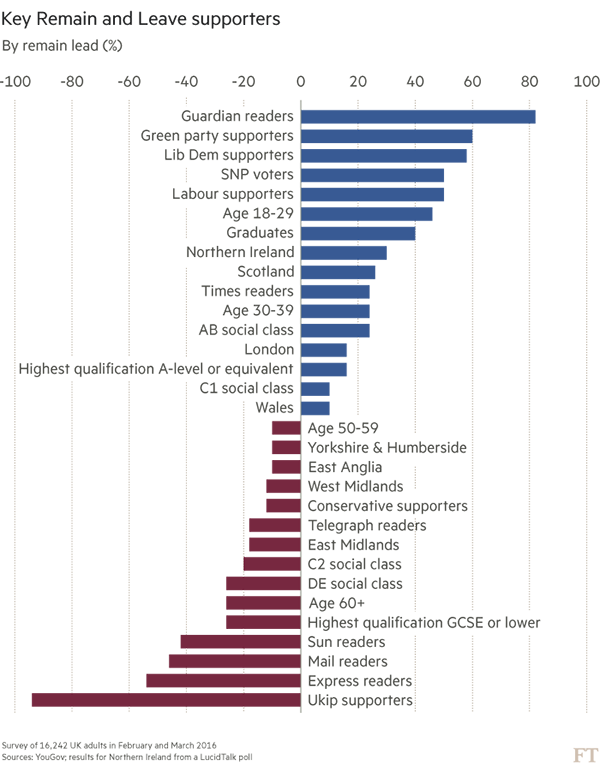

On one side are older voters, the more disadvantaged and the less-well educated. On the other, are better off younger people and inhabitants of metropolitan London.

These are the dividing lines in June 23’s historic referendum to decide Britain’s place in the EU, a fight that in large part cuts across traditional party lines.

At the heart of the contest is a struggle for Conservative-leaning voters with rallying cries that traditionally appeal to centre-right voters, notably immigration and the economy.

Many of their votes are still up for grabs. In a recent survey by Ipsos Mori, a third of Conservative voters said they may yet change their minds, compared with 18 per cent of Labour supporters and only 7 per cent of voters for the anti-EU UK Independence party.

Such considerations help explain the tenor of the campaign. Wavering Conservative voters account for much of the intended audience of both the Leave camp’s emphasis on immigration and Remain’s warnings about the supposed economic impact of a break-up with Europe.

“We could not win without immigration,” says one senior official who favours Brexit, as withdrawal from the EU is known, referring to widespread concern over record influxes of EU migrants.

So far, however, the Leave campaign has struggled to win the economic argument — and that could prove fatal.

“Immigration is clearly an important card, but it doesn’t look like it will be sufficient on its own,” says Prof John Curtice, a veteran polling expert.

According to an average of polls compiled by Mr Curtice, in AprilTory supporters favoured Brexit by 55 per cent to 45, but in May the split had evened out to 50-50. Opinion among Labour voters, about 70 per cent of whom support EU membership, barely changed.

The demographics of the vote

The Remain camp may also be helped by better organisation. An analysis by Matthew Goodwin of Kent university indicates that the pro-EU campaign is consistently holding more campaign events — such as canvassing, leafleting and rallies — than the Brexit cause, with the gap increasing in recent weeks.

Mr Goodwin adds that Remain is also better targeting such events, locating a third of them in densely populated, pro-EU areas, which could provide a bountiful supply of votes. By contrast, only 3 per cent of Leave events took place in densely populated, highly Eurosceptic areas.

Indeed, as the Remain and Leave camps head towards the final stretch, identifying key areas of support — and ensuring that sympathetic voters flock to the polls — is just as important as winning the argument and changing minds.

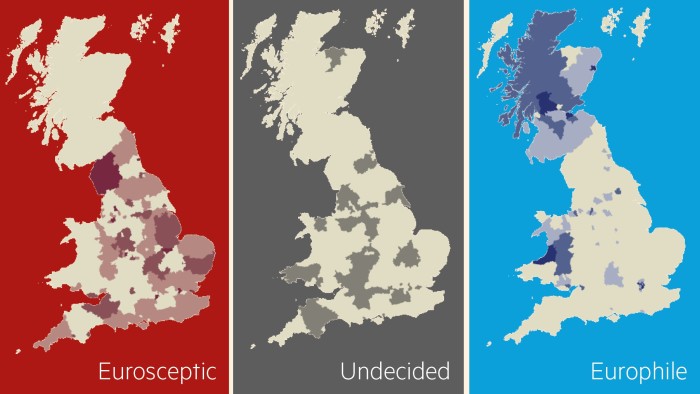

According to YouGov, the polling group, the Remain campaign’s strongest geographical areas of support are Northern Ireland, which receives large amounts of EU financial aid, and Scotland and London, two of the UK’s richest regions.

————————-

UK’s EU Referendum: How people would vote

For a more detailed summary of opinion polling visit the FT’s Brexit poll tracker page

————————-

The inhabitants of less prosperous regions such as the East Midlands, Yorkshire and Humberside are more likely to favour Brexit, as are those from areas of high immigration such as East Anglia.

Battlegrounds that are finely poised between Leave and Remain range from Surrey in the south-east to Worcestershire in the West Midlands and East Riding in Yorkshire.

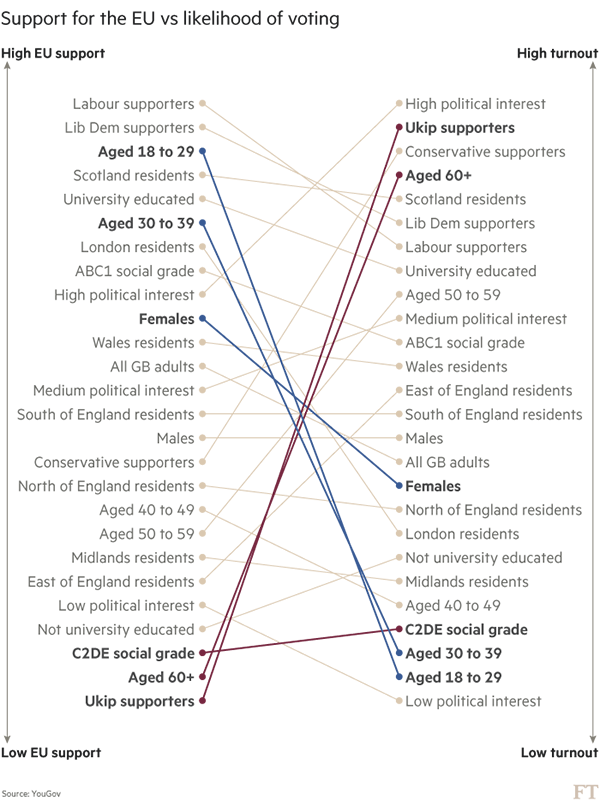

Despite pollsters’ widely shared findings that older people are more likely to favour Britain leaving the EU, analysts caution that such voters’ higher turnout rates may not automatically translate to an advantage for the Leave camp. This is because poorer people, also a mainstay of Brexit support, often stay away from the polling booth.

“We have more old people on our side but their old people are more likely to vote,” says one Leave campaign strategist.

Generally, the higher the turnout, the more likely the campaign to stay in the EU is to succeed. A rough rule of thumb is that an overall participation rate of 65 per cent or more is good news for the Remain camp, since the Leave campaign’s more enthusiastic supporters are likely to vote in any case. But experts emphasise that what really matters is who exactly turns out to vote.

Remain claims momentum

Leave campaigners admit they are struggling to win over what they claim to be the 20 per cent of voters who “want to leave but are worried”.

They hold out hope that a series of economic warnings by David Cameron, prime minister, has not yet definitively won the day.

A recent Ipsos Mori survey found that only 22 per cent of respondents thought their standard of living would suffer as a result of Brexit, while 58 per cent considered that it would remain the same.

But poll data indicate that the importance of the economy to the vote may in fact be underestimated.

Anthony Wells of YouGov argues that while voters have a rather “nebulous” idea that mass immigration is changing the country for the worse, they cast their votes on issues of more pressing concern to their daily lives, such as jobs and personal prosperity.

For example, in September 2015 after a summer dominated by Europe’s refugee crisis, 71 per cent of voters said that immigration was one of the three biggest issues facing Britain, compared with just 35 per cent citing the economy.

But when respondents were asked instead to identify the biggest issue facing themselves and their families, only 24 per cent mentioned immigration while 40 per cent said the economy.

Pollsters say answers to such questions could well hold the key to the result of this month’s vote.

Mr Wells notes that economic turmoil was widely seen as the decisive factor in persuading Scots to vote against independence in 2014 and the Conservatives’ victory in Britain’s 2015 general election.

“The experience of Scotland and the general election is that economic fear wins out,” he says. “The economic arguments are moving in favour of Remain. When it comes down to it, head normally wins out over heart.”

————————-

UK’s EU referendum: full coverage and analysis

View the FT’s comprehensive guide to the vote on whether Britain should stay in Europe, with all the latest news, analysis and commentary from both sides of the debate. See more

————————-

Comments