World economy feels the impact when China takes a knock

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If the past six months’ economic news has taught the world one thing, it is that a bump in China’s economy cannot be ignored. The question is whether the rest of the world feels a gentle ripple or a tidal wave.

China is now the world’s largest economy measured by the quantity of goods and services produced, and the International Monetary Fund expects the country to account for almost 18 per cent of world economic activity in 2016. This implies that the drop in its growth rate from an expansion of more than 10 per cent in 2010 to 6.3 per cent expected this year has directly knocked about 0.75 percentage points off the global growth rate.

The spillover effects, however, are much broader than this direct calculation of China’s importance. Maury Obstfeld, the IMF chief economist, says he is most worried about these knock-on effects in 2016.

“The global spillovers from China’s reduced rate of growth . . . have been much larger than we would have anticipated,” he said this week.

What are the channels through which China affects the global economy?

Trade and exchange rates

Although China’s import volumes are still growing, a weaker than expected economy directly cuts the export growth of countries that are highly dependent on Chinese demand for oil, metals, materials and machine tools in its industrial centres.

Neighbours with integrated supply chains such as Japan and South Korea are deeply affected, Germany is most at risk in Europe as a producer of capital goods to China and commodity specialists such as Australia also stand in the firing line. But direct trade effects are rarely an immediate game changer and as the world’s largest net exporter, China is more dependent on the world economy than it is on China.

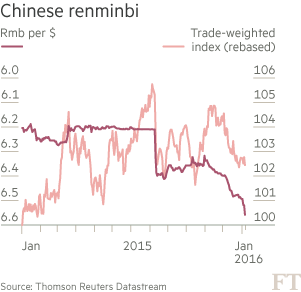

One way to amplify the trade effects would be through a massive depreciation of the renminbi in an attempt to revive Chinese export-led growth. The renminbi has dropped 6 per cent against the US dollar since July, spreading fears of a currency war, but against its wider trading partners China’s exchange rate appreciated marginally in 2015. A currency war still seems some distance away.

Oil and commodities

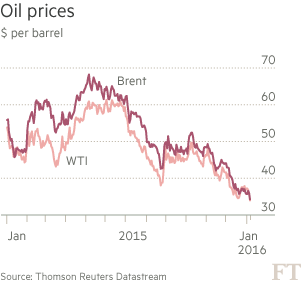

Worries about China’s economic strength is part of the reason for the renewed drop in oil prices, dragging Brent crude down to an 11-year low, below $33 a barrel on Thursday. Weakness in oil and other commodity prices has pushed Russia and Brazil into deep recessions and hit the finances of Gulf states.

Global investment in oil extraction has slumped, undermining parts of the US economy and sectors in other countries hosting capital goods manufacturers.

But low oil and commodity prices mostly redistribute economic prospects around the world rather than diminish them. Oil producers lose, but consumers, including those in China itself, gain from the equivalent of a tax cut.

The IMF still thinks the net effect of lower commodity prices is positive. At worst, it damps the otherwise more serious effects of lower-than-expected Chinese demand growth.

Inflation and monetary policy

Whether it is a weaker renminbi making Chinese goods more affordable, lower commodity prices or reduced demand in the world economy, a China slowdown weakens inflationary pressures around the world, triggering fears of a global deflationary spiral and debt defaults.

But, if advanced economies genuinely appear to be suffering from flatlining prices, low inflation also gives policymakers additional leeway to keep monetary policy looser for longer in the US and UK and to add to quantitative easing in Europe.

Fears of a downward spiral are exaggerated. Many of these lower prices also increase the prosperity of consumers around the world and should boost demand, thereby offsetting Chinese deflationary forces.

Confidence

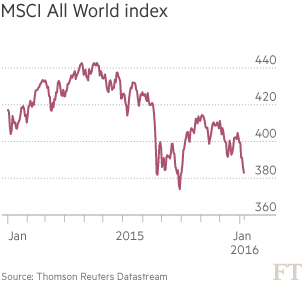

While all the other effects of China on the global economy are reasonably predictable and potentially have offsetting benefits, the pernicious effect of weaker confidence has the greatest potential to shock.

Whether it is through global financial market turmoil, the willingness of companies to invest or the desire of households to tighten their belts, confidence in the security of the global economy is both vital for prosperity and almost entirely unpredictable.

At best confidence can return quickly without much effect on the global economic outlook, as it did after last summer’s turmoil also centred on China. But as 2008 taught everyone, once confidence disappears, the effect on the global economy can be massive — potentially bringing down companies, banks, markets and the financial system. It is no wonder economists such as Andy Haldane, Bank of England chief economist, talk about emerging markets as potentially being the third leg of the global financial crisis.

The wider effect of China’s fresh troubles will therefore depend on whether people and companies decide to wait before taking a decision to spend and invest — or carry on regardless.

Comments