How politicians poisoned statistics

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In January 2015, a few months before the British general election, a proud newspaper resigned itself to the view that little good could come from the use of statistics by politicians. An editorial in the Guardian argued that in a campaign that would be “the most fact-blitzed in history”, numerical claims would settle no arguments and persuade no voters. Not only were numbers useless for winning power, it added, they were useless for wielding it, too. Numbers could tell us little. “The project of replacing a clash of ideas with a policy calculus was always dubious,” concluded the newspaper. “Anyone still hankering for it should admit their number’s up.”

This statistical capitulation was a dismaying read for anyone still wedded to the idea — apparently a quaint one — that gathering statistical information might help us understand and improve our world. But the Guardian’s cynicism can hardly be a surprise. It is a natural response to the rise of “statistical bullshit” — the casual slinging around of numbers not because they are true, or false, but to sell a message.

Politicians weren’t always so ready to use numbers as part of the sales pitch. Recall Ronald Reagan’s famous suggestion to voters on the eve of his landslide defeat of President Carter: “Ask yourself, ‘Are you better off now than you were four years ago?’” Reagan didn’t add any statistical garnish. He knew that voters would reach their own conclusions.

The British election campaign of spring last year, by contrast, was characterised by a relentless statistical crossfire. The shadow chancellor of the day, Ed Balls, declared that a couple with children (he didn’t say which couple) had lost £1,800 thanks to the government’s increase in value added tax. David Cameron, the prime minister, countered that 94 per cent of working households were better off thanks to recent tax changes, while the then deputy prime minister Nick Clegg was proud to say that 27 million people were £825 better off in terms of the income tax they paid.

Could any of this be true? Yes — all three claims were. But Ed Balls had reached his figure by summing up extra VAT payments over several years, a strange method. If you offer to hire someone for £100,000, and then later admit you meant £25,000 a year for a four-year contract, you haven’t really lied — but neither have you really told the truth. And Balls had looked only at one tax. Why not also consider income tax, which the government had cut? Clegg boasted about income-tax cuts but ignored the larger rise in VAT. And Cameron asked to be evaluated only on his pre-election giveaway budget rather than the tax rises he had introduced earlier in the parliament — the equivalent of punching someone on the nose, then giving them a bunch of flowers and pointing out that, in floral terms, they were ahead on the deal.

Each claim was narrowly true but broadly misleading. Not only did the clashing numbers confuse but none of them helped answer the crucial question of whether Cameron and Clegg had made good decisions in office.

To ask whether the claims were true is to fall into a trap. None of these politicians had any interest in playing that game. They were engaged in another pastime entirely.

. . .

Thirty years ago, the Princeton philosopher Harry Frankfurt published an essay in an obscure academic journal, Raritan. The essay’s title was “On Bullshit”. (Much later, it was republished as a slim volume that became a bestseller.) Frankfurt was on a quest to understand the meaning of bullshit — what was it, how did it differ from lies, and why was there so much of it about?

Frankfurt concluded that the difference between the liar and the bullshitter was that the liar cared about the truth — cared so much that he wanted to obscure it — while the bullshitter did not. The bullshitter, said Frankfurt, was indifferent to whether the statements he uttered were true or not. “He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.”

Statistical bullshit is a special case of bullshit in general, and it appears to be on the rise. This is partly because social media — a natural vector for statements made purely for effect — are also on the rise. On Instagram and Twitter we like to share attention-grabbing graphics, surprising headlines and figures that resonate with how we already see the world. Unfortunately, very few claims are eye-catching, surprising or emotionally resonant because they are true and fair. Statistical bullshit spreads easily these days; all it takes is a click.

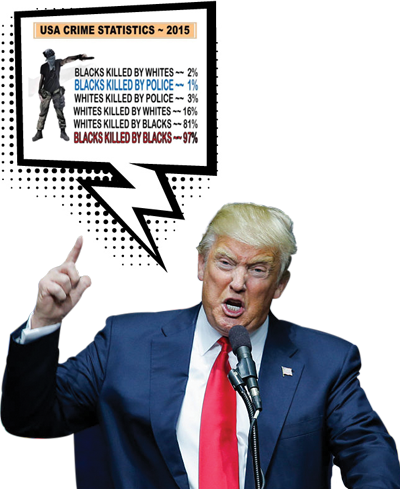

Consider a widely shared list of homicide “statistics” attributed to the “Crime Statistics Bureau — San Francisco”, asserting that 81 per cent of white homicide victims were killed by “blacks”. It takes little effort to establish that the Crime Statistics Bureau of San Francisco does not exist, and not much more digging to discover that the data are utterly false. Most murder victims in the United States are killed by people of their own race; the FBI’s crime statistics from 2014 suggest that more than 80 per cent of white murder victims were killed by other white people.

Somebody, somewhere, invented the image in the hope that it would spread, and spread it did, helped by a tweet from Donald Trump, the current frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination, that was retweeted more than 8,000 times. One can only speculate as to why Trump lent his megaphone to bogus statistics, but when challenged on Fox News by the political commentator Bill O’Reilly, he replied, “Hey, Bill, Bill, am I gonna check every statistic?”

Harry Frankfurt’s description of the bullshitter would seem to fit Trump perfectly: “He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly.”

While we can’t rule out the possibility that Trump knew the truth and was actively trying to deceive his followers, a simpler explanation is that he wanted to win attention and to say something that would resonate with them. One might also guess that he did not check whether the numbers were true because he did not much care one way or the other. This is not a game of true and false. This is a game of politics.

. . .

While much statistical bullshit is careless, it can also be finely crafted. “The notion of carefully wrought bullshit involves . . . a certain inner strain,” wrote Harry Frankfurt but, nevertheless, the bullshit produced by spin-doctors can be meticulous. More conventional politicians than Trump may not much care about the truth but they do care about being caught lying.

Carefully wrought bullshit was much in evidence during last year’s British general election campaign. I needed to stick my nose in and take a good sniff on a regular basis because I was fact-checking on behalf of the BBC’s More or Less programme. Again and again I would find myself being asked on air, “Is that claim true?” and finding that the only reasonable answer began with “It’s complicated”.

Take Ed Miliband’s claim before the last election that “people are £1,600 a year worse off” than they were when the coalition government came to power. Was that claim true? Arguably, yes.

But we need to be clear that by “people”, the then Labour leader was excluding half the adult population. He was not referring to pensioners, benefit recipients, part-time workers or the self-employed. He meant only full-time employees, and, more specifically, only their earnings before taxes and benefits.

Even this narrower question of what was happening to full-time earnings is a surprisingly slippery one. We need to take an average, of course. But what kind of average? Labour looked at the change in median wages, which were stagnating in nominal terms and falling after inflation was taken into account.

That seems reasonable — but the median is a problematic measure in this case. Imagine nine people, the lowest-paid with a wage of £1, the next with a wage of £2, up to the highest-paid person with a wage of £9. The median wage is the wage of the person in the middle: it’s £5.

Now imagine that everyone receives a promotion and a pay rise of £1. The lowly worker with a wage of £1 sees his pay packet double to £2. The next worker up was earning £2 and now she gets £3. And so on. But there’s also a change in the composition of the workforce: the best-paid worker retires and a new apprentice is hired at a wage of £1. What’s happened to people’s pay? In a sense, it has stagnated. The pattern of wages hasn’t changed at all and the median is still £5.

But if you asked the individual workers about their experiences, they would all tell you that they had received a generous pay rise. (The exceptions are the newly hired apprentice and the recent retiree.) While this example is hypothetical, at the time Miliband made his comments something similar was happening in the real labour market. The median wage was stagnating — but among people who had worked for the same employer for at least a year, the median worker was receiving a pay rise, albeit a modest one.

Another source of confusion: if wages for the low-paid and the high-paid are rising but wages in the middle are sagging, then the median wage can fall, even though the median wage increase is healthy. The UK labour market has long been prone to this kind of “job polarisation”, where demand for jobs is strongest for the highest and lowest-paid in the economy. Job polarisation means that the median pay rise can be sizeable even if median pay has not risen.

Confused? Good. The world is a complicated place; it defies description by sound bite statistics. No single number could ever answer Ronald Reagan’s question — “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” — for everyone in a country.

So, to produce Labour’s figure of “£1,600 worse off”, the party’s press office had to ignore the self-employed, the part-timers, the non-workers, compositional effects and job polarisation. They even changed the basis of their calculation over time, switching between different measures of wages and different measures of inflation, yet miraculously managing to produce a consistent answer of £1,600. Sometimes it’s easier to make the calculation produce the number you want than it is to reprint all your election flyers.

Such careful statistical spin-doctoring might seem a world away from Trump’s reckless retweeting of racially charged lies. But in one sense they were very similar: a political use of statistics conducted with little interest in understanding or describing reality. Miliband’s project was not “What is the truth?” but “What can I say without being shown up as a liar?”

Unlike the state of the UK job market, his incentives were easy to understand. Miliband needed to hammer home a talking point that made the government look bad. As Harry Frankfurt wrote back in the 1980s, the bullshitter “is neither on the side of the true nor on the side of the false. His eye is not on the facts at all . . . except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says.”

Such complexities put fact-checkers in an awkward position. Should they say that Ed Miliband had lied? No: he had not. Should they say, instead, that he had been deceptive or misleading? Again, no: it was reasonable to say that living standards had indeed been disappointing under the coalition government.

Nevertheless, there was a lot going on in the British economy that the figure omitted — much of it rather more flattering to the government. Full Fact, an independent fact-checking organisation, carefully worked through the paper trail and linked to all the relevant claims. But it was powerless to produce a fair and representative snapshot of the British labour market that had as much power as Ed Miliband’s seven-word sound bite. No such snapshot exists. Truth is usually a lot more complicated than statistical bullshit.

. . .

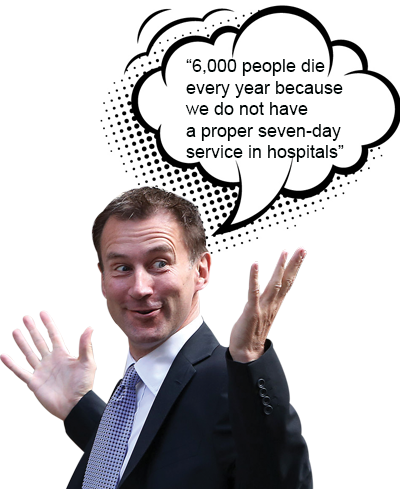

On July 16 2015, the UK health secretary Jeremy Hunt declared: “Around 6,000 people lose their lives every year because we do not have a proper seven-day service in hospitals. You are 15 per cent more likely to die if you are admitted on a Sunday compared to being admitted on a Wednesday.”

This was a statistic with a purpose. Hunt wanted to change doctors’ contracts with the aim of getting more weekend work out of them, and bluntly declared that the doctors’ union, the British Medical Association, was out of touch and that he would not let it block his plans: “I can give them 6,000 reasons why.”

Despite bitter opposition and strike action from doctors, Hunt’s policy remained firm over the following months. Yet the numbers he cited to support it did not. In parliament in October, Hunt was sticking to the 15 per cent figure, but the 6,000 deaths had almost doubled: “According to an independent study conducted by the BMJ, there are 11,000 excess deaths because we do not staff our hospitals properly at weekends.”

Arithmetically, this was puzzling: how could the elevated risk of death stay the same but the number of deaths double? To add to the suspicions about Hunt’s mathematics, the editor-in-chief of the British Medical Journal, Fiona Godlee, promptly responded that the health secretary had publicly misrepresented the BMJ research.

Undaunted, the health secretary bounced back in January with the same policy and some fresh facts: “At the moment we have an NHS where if you have a stroke at the weekends, you’re 20 per cent more likely to die. That can’t be acceptable.”

All this is finely wrought bullshit — a series of ever-shifting claims that can be easily repeated but are difficult to unpick. As Hunt jumped from one form of words to another, he skipped lightly ahead of fact-checkers as they tried to pin him down. Full Fact concluded that Hunt’s statement about 11,000 excess deaths had been untrue, and asked him to correct the parliamentary record. His office responded with a spectacular piece of bullshit, saying (I paraphrase) that whether or not the claim about 11,000 excess deaths was true, similar claims could be made that were.

So, is it true? Do 6,000 people — or 11,000 — die needlessly in NHS hospitals because of poor weekend care? Nobody knows for sure; Jeremy Hunt certainly does not. It’s not enough to show that people admitted to hospital at the weekend are at an increased risk of dying there. We need to understand why — a question that is essential for good policy but inconvenient for politicians.

One possible explanation for the elevated death rate for weekend admissions is that the NHS provides patchy care and people die as a result. That is the interpretation presented as bald fact by Jeremy Hunt. But a more straightforward explanation is that people are only admitted to hospital at the weekend if they are seriously ill. Less urgent cases wait until weekdays. If weekend patients are sicker, it is hardly a surprise that they are more likely to die. Allowing non-urgent cases into NHS hospitals at weekends wouldn’t save any lives, but it would certainly make the statistics look more flattering. Of course, epidemiologists try to correct for the fact that weekend patients tend to be more seriously ill, but few experts have any confidence that they have succeeded.

A more subtle explanation is that shortfalls in the palliative care system may create the illusion that hospitals are dangerous. Sometimes a patient is certain to die, but the question is where — in a hospital or a palliative hospice? If hospice care is patchy at weekends then a patient may instead be admitted to hospital and die there. That would certainly reflect poor weekend care. It would also add to the tally of excess weekend hospital deaths, because during the week that patient would have been admitted to, and died in, a palliative hospice. But it is not true that the death was avoidable.

Does it seem like we’re getting stuck in the details? Well, yes, perhaps we are. But improving NHS care requires an interest in the details. If there is a problem in palliative care hospices, it will not be fixed by improving staffing in hospitals.

“Even if you accept that there’s a difference in death rates,” says John Appleby, the chief economist of the King’s Fund health think-tank, “nobody is able to say why it is. Is it lack of diagnostic services? Lack of consultants? We’re jumping too quickly from a statistic to a solution.”

This matters — the NHS has a limited budget. There are many things we might want to spend money on, which is why we have the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) to weigh up the likely benefits of new treatments and decide which offer the best value for money.

Would Jeremy Hunt’s push towards a seven-day NHS pass the Nice cost-benefit threshold? Probably not. Our best guess comes from a 2015 study by health economists Rachel Meacock, Tim Doran and Matt Sutton, which estimates that the NHS has many cheaper ways to save lives. A more comprehensive assessment might reach a different conclusion but we don’t have one because the Department for Health, oddly, hasn’t carried out a formal health impact assessment of the policy it is trying to implement.

This is a depressing situation. The government has devoted considerable effort to producing a killer number: Jeremy Hunt’s “6,000 reasons” why he won’t let the British Medical Association stand in his way. It continues to produce statistical claims that spring up like hydra heads: when one claim is discredited, Hunt’s office simply asserts that another one can be found to take its place. Yet the government doesn’t seem to have bothered to gather the statistics that would actually answer the question of how the NHS could work better.

This is the real tragedy. It’s not that politicians spin things their way — of course they do. That is politics. It’s that politicians have grown so used to misusing numbers as weapons that they have forgotten that used properly, they are tools.

. . .

You complain that your report would be dry. The dryer the better. Statistics should be the dryest of all reading,” wrote the great medical statistician William Farr in a letter in 1861. Farr sounds like a caricature of a statistician, and his prescription — convey the greatest possible volume of information with the smallest possible amount of editorial colour — seems absurdly ill-suited to the modern world.

But there is a middle ground between the statistical bullshitter, who pays no attention to the truth, and William Farr, for whom the truth must be presented without adornment. That middle ground is embodied by the recipient of William Farr’s letter advising dryness. She was the first woman to be elected to the Royal Statistical Society: Florence Nightingale.

Nightingale is the most celebrated nurse in British history, famous for her lamplit patrols of the Barrack Hospital in Scutari, now a district of Istanbul. The hospital was a death trap, with thousands of soldiers from the Crimean front succumbing to typhus, cholera and dysentery as they tried to recover from their wounds in cramped conditions next to the sewers. Nightingale, who did her best, initially believed that the death toll was due to lack of food and supplies. Then, in the spring of 1855, a sanitary commission sent from London cleaned up the hospital, whitewashing the walls, carting away filth and dead animals and flushing out the sewers. The death rate fell sharply.

Nightingale returned to Britain and reviewed the statistics, concluding that she had paid too little attention to sanitation and that most military and medical professions were making the same mistake, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths. She began to campaign for better public health measures, tighter laws on hygiene in rented properties, and improvements to sanitation in barracks and hospitals across the country. In doing so, a mere nurse had to convince the country’s medical and military establishments, led by England’s chief medical officer, John Simon, that they had been doing things wrong all their lives.

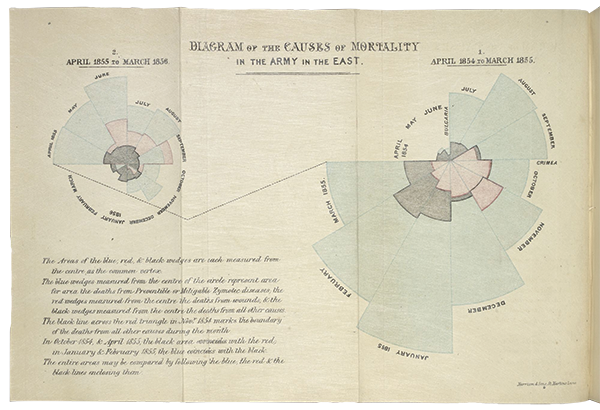

A key weapon in this lopsided battle was statistical evidence. But Nightingale disagreed with Farr on how that evidence should be presented. “The dryer the better” would not serve her purposes. Instead, in 1857, she crafted what has become known as the Rose Diagram, a beautiful array of coloured wedges showing the deaths from infectious diseases before and after the sanitary improvements at Scutari.

The Rose Diagram isn’t a dry presentation of statistical truth. It tells a story. Its structure divides the death toll into two periods — before the sanitary improvements, and after. In doing so, it highlights a sharp break that is less than clear in the raw data. And the Rose Diagram also gently obscures other possible interpretations of the numbers — that, for example, the death toll dropped not because of improved hygiene but because winter was over. The Rose Diagram is a marketing pitch for an idea. The idea was true and vital, and Nightingale’s campaign was successful. One of her biographers, Hugh Small, argues that the Rose Diagram ushered in health improvements that raised life expectancy in the UK by 20 years and saved millions of lives.

What makes Nightingale’s story so striking is that she was able to see that statistics could be tools and weapons at the same time. She educated herself using the data, before giving it the makeover it required to convince others. Though the Rose Diagram is a long way from “the dryest of all reading”, it is also a long way from bullshit. Florence Nightingale realised that the truth about public health was so vital that it could not simply be recited in a monotone. It needed to sing.

. . .

The idea that a graph could change the world seems hard to imagine today. Cynicism has set in about statistics. Many journalists draw no distinction between a systematic review of peer-reviewed evidence and a survey whipped up in an afternoon to sell biscuits or package holidays: it’s all described as “new research”. Politicians treat statistics not as the foundation of their argument but as decoration — “spray-on evidence” is the phrase used by jaded civil servants. But a freshly painted policy without foundations will not last long before the cracks show through.

“Politicians need to remember: there is a real world and you want to try to change it,” says Will Moy, the director of Full Fact. “At some stage you need to engage with the real world — and that is where the statistics come in handy.”

That should be no problem, because it has never been easier to gather and analyse informative statistics. Nightingale and Farr could not have imagined the data that modern medical researchers have at their fingertips. The gold standard of statistical evidence is the randomised controlled trial, because using a randomly chosen control group protects against biased or optimistic interpretations of the evidence. Hundreds of thousands of such trials have been published, most of them within the past 25 years. In non-medical areas such as education, development aid and prison reform, randomised trials are rapidly catching on: thousands have been conducted. The British government, too, has been supporting policy trials — for example, the Education Endowment Foundation, set up with £125m of government funds just five years ago, has already backed more than 100 evaluations of educational approaches in English schools. It favours randomised trials wherever possible.

The frustrating thing is that politicians seem quite happy to ignore evidence — even when they have helped to support the researchers who produced it. For example, when the chancellor George Osborne announced in his budget last month that all English schools were to become academies, making them independent of the local government, he did so on the basis of faith alone. The Sutton Trust, an educational charity which funds numerous research projects, warned that on the question of whether academies had fulfilled their original mission of improving failing schools in poorer areas, “our evidence suggests a mixed picture”. Researchers at the LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance had a blunter description of Osborne’s new policy: “a non-evidence based shot in the dark”.

This should be no surprise. Politicians typically use statistics like a stage magician uses smoke and mirrors. Over time, they can come to view numbers with contempt. Voters and journalists will do likewise. No wonder the Guardian gave up on the idea that political arguments might be settled by anything so mundane as evidence. The spin-doctors have poisoned the statistical well.

But despite all this despair, the facts still matter. There isn’t a policy question in the world that can be settled by statistics alone but, in almost every case, understanding the statistical background is a tremendous help. Hetan Shah, the executive director of the Royal Statistical Society, has lost count of the number of times someone has teased him with the old saying about “lies, damned lies and statistics”. He points out that while it’s easy to lie with statistics, it’s even easier to lie without them.

Perhaps the lies aren’t the real enemy here. Lies can be refuted; liars can be exposed. But bullshit? Bullshit is a stickier problem. Bullshit corrodes the very idea that the truth is out there, waiting to be discovered by a careful mind. It undermines the notion that the truth matters. As Harry Frankfurt himself wrote, the bullshitter “does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.”

Tim Harford is the author of ‘The Undercover Economist Strikes Back’. Twitter @TimHarford

Three pieces of Brexit Bullshit

A referendum on UK membership of the European Union is scheduled for June 23: dodgy statistics ahoy.

“Ten Commandments — 179 words. Gettysburg address — 286 words. US Declaration of Independence — 1,300 words. EU regulations on the sale of cabbage — 26,911 words”

Variants of this claim have been circulating online and in print. It turns out that the “cabbage memo” is a longstanding urban myth that can be traced back to the US during the second world war. Variants have been used to berate bureaucrats on both sides of the Atlantic ever since.

Part of the bullshit here is that nobody ever stops to ask how many words might be appropriate for rules on fresh produce. Red Tractor Assurance, the British farm and food standards scheme, publishes 56 different protocols on fresh produce alone. The cabbage protocol is 28 pages long; there is a separate 28-page protocol on pak choi and choi sum. None of this has anything to do with the EU.

Three million jobs depend on the EU

This claim is popular among “Remain” advocates — most famously the former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg. What makes this claim bullshit is that it could easily be true, or utterly false, and it all hangs on the definition of “depend”.

The claim is that “up to 3.2 million jobs” were directly linked to exports of goods and services to other EU countries. That number passes a quick reality check: it’s about 10 per cent of UK jobs, and UK exports to the EU are about 10 per cent of the UK economy.

But even if “up to” 3.2 million jobs depend on trade with the EU, that does not mean they depend on membership of the EU. Nobody proposes — or expects — that trade with the EU will just stop. Three million jobs might well be destroyed if continental Europe was to sink beneath the waves like Atlantis, but that is not what the referendum is about.

EU membership costs £55m a day

This one is from Ukip leader Nigel Farage, who says membership amounts to more than £20bn a year. In fact, the UK paid £14.3bn to the EU in 2014 and got £6bn back. The net membership fee, then, was £8.3bn, less than half Farage’s number.

But even the correct number is little use without context. It is, for example, just over 1 per cent of UK public spending. Not nothing, but not everything either. And non-member states such as Norway and Switzerland pay large sums to the EU to retain access to the single market, so Brexit would not make this bill disappear.

The membership fee is small relative to the plausible costs and benefits of EU membership, positive or negative. If EU membership is good for Britain then £8.3bn is cheap. And if the EU is holding Britain back, then a few billion on membership is the least of our worries.

Illustrations by Pâté

Photographs: Getty

Letters in response to this article:

Press and consultants share in statistical fiddles / From CG Pradeep Kumar

It is working conditions that concern doctors / From Dr Thomas Mount

Comments