What has the EU done for the UK?

Mike Matthews, the gritty managing director of a car parts company that once came close to collapse, has seen at first hand how the EU has tested Britain’s economy by unleashing greater competition.

And yet the experiences of his company, Nifco UK, are the reason why he said he would vote Remain in last June’s referendum.

His is a story that goes to the heart of the history of the UK in Europe and the long, unresolved debate over the economic benefits of membership. In the third part of a series on the implications of Brexit, the Financial Times looks at how the EU has changed the British economy.

A decade ago, Nifco UK was in deep trouble. It had lost control of costs in the highly competitive business to supply UK-based car plants that sell across Europe.

Rivals in Germany and elsewhere threatened to devour the company’s market for handles, plastic pipes in car engines and seatbelt covers. Nifco UK badly needed a turnround plan.

The predicament was the same that thousands of British companies have confronted since the UK joined the European bloc in 1973, ending long years of preferential ties with the country’s former colonies.

Greater competition from the continent proved difficult to adjust to, despite the rewards of access to the biggest market in the world. “We don’t have price increases,” Mr Matthews says, referring to the pressure to stay competitive even when the price of raw materials goes up. “Every year we have to give cost reductions.”

In response, Nifco UK modernised, at its base near Stockton-on-Tees, in one of Britain’s most deprived regions. The group’s Japanese parent invested in personnel, plant and research. Today even the reception desk is automated and gleaming machinery looms over workers on the factory floor. The company has moved ahead of its German competitors, acquiring plants in Germany, Spain and Poland, and supplying 286 car plants worldwide.

To Mr Matthews, access to the EU single market is vital. “If you’re an ambitious business, do you want a 1.6m [car] market or a 18m potential market?” he says. But many other executives complain that EU regulations have held them back.

For decades, British companies have struggled to respond to competition from elsewhere in the EU, with some household names disappearing. British Leyland, the once mighty car manufacturer, and ICI, the industrial conglomerate, are just two of the titans that have collapsed. But those that have survived have often emerged stronger.

Perhaps the biggest issue in the June 23 referendum was the question of whether 43 years in the EU have helped or hurt the UK economy.

Many economists contend what matters most is not funds transferred between Brussels and London, or even claims of jobs created or destroyed. Instead, the central issue is how EU membership has changed the shape of the British economy — its competitiveness and openness to other markets — through the impact on thousands of companies such as Nifco.

“Competition forced these guys to improve or exit,” said Professor Nick Bloom of Stanford University. “The single European market increased competition and forced British firms to increase the level of innovation.”

The growth effect

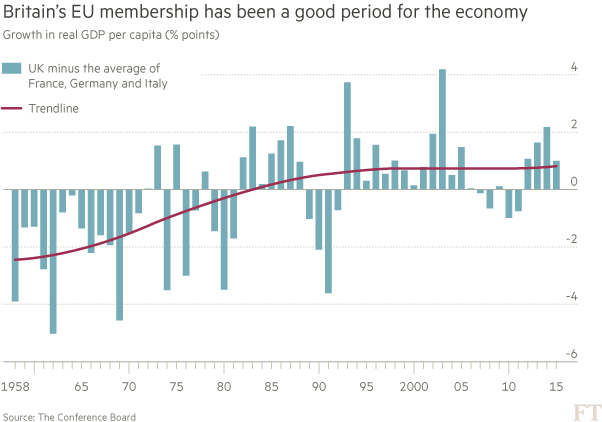

Britain joined what was then the European Economic Community in 1973 as the sick man of Europe. By the late 1960s, France, West Germany and Italy — the three founder members closest in size to the UK — produced more per person than it did and the gap grew larger every year. Between 1958, when the EEC was set up, and Britain’s entry in 1973, gross domestic product per head rose 95 per cent in these three countries compared with only 50 per cent in Britain.

After becoming an EEC member, Britain slowly began to catch up. Gross domestic product per person has grown faster than Italy, Germany and France in the more than 40 years since. By 2013, Britain became more prosperous than the average of the three other large European economies for the first time since 1965.

Professor Nauro Campos of Brunel University has estimated how Britain would have fared if it had not joined the common market. He and his colleagues found the best approximation to Britain’s pre-1973 economic performance to be a combination of New Zealand and Argentina, which like the UK fell behind the US and continental Europe.

During the next 40 years, the UK economy outperformed those two countries by 23 per cent. According to the findings, Britain’s performance also surpassed the vast majority of 1,000 other combinations of countries whose record had previously resembled its own.

Such studies highlight two main periods when prosperity increased: in the 1970s, soon after the UK joined, and after the EU opened its single market in goods in 1992. But, because it is difficult to distinguish cause from correlation, the UK’s post-1973 rebound does not itself definitively establish that EU membership made the country more productive — the fundamental issue at stake. Ruth Lea, economic adviser to Arbuthnot Securities, a private bank, said the leading cause of its reversal in fortunes was in fact “a certain lady from Finchley” — Margaret Thatcher, who privatised state-owned companies, weakened the unions and deregulated the City of London.

Boosted trade

Most economists have little doubt that Britain’s membership of the EU has translated into more trade.

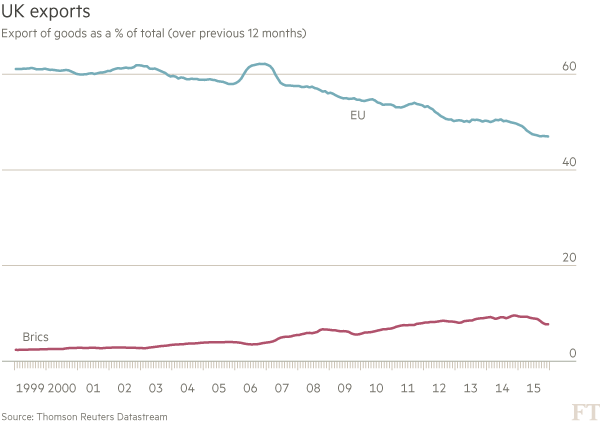

Daniel Vernazza of UniCredit has shown that UK trade with EU partners grew faster after 1973 than it did with the remaining countries in the European Free Trade Association, the grouping to which Britain previously belonged. His work underlines that harmonising regulations — an effort at the heart of the EU endeavour — was often much more effective in boosting trade than was lowering tariffs.

Professor Nick Crafts of Warwick University, Britain’s pre-eminent economic historian, adds that opening to trade allowed the UK to bounce back after falling behind its neighbours. “Britain’s really, really big problem in the 1960s was very weak competition,” he said. “Trade liberalisation was a major factor in improving competition . . . It removed weak firms, made management better and improved industrial relations — more than Thatcher.”

Data compiled by Rebecca Driver of the consultancy Analytically Driven highlight a causal link between Britain’s greater openness to trade since 1973 and its subsequent specialisation in high productivity sectors, including finance, high-tech manufacturing and business services. Ms Driver said the 11 per cent of British companies that trade internationally are responsible for 60 per cent of the UKs productivity gains.

“These companies prefer large geographically concentrated markets with strong unified regulations,” she adds. “For the UK, that is the EU”. In other words, trade drives competition and growth. Since 1993, the UK has been the bloc’s top recipient of inward foreign direct investment, according to the UN.

The fallout

Today one in 20 UK residents was born in another EU country. But numerous studies have shown that most gains from immigration have fallen to the immigrants themselves. Apart from a net benefit to public finances of importing workers, free movement has not obviously increased British prosperity.

When the global financial crisis hit, Britain also found itself exposed to bad foreign assets held by UK banks.

Some Eurosceptics say Britain stands a better chance of growth if it looks beyond the sluggish economies of the EU. But this is a claim about the future, predicated on trading relationships that do not yet exist, rather than an analysis of the past.

For almost half a century, Britain has benefited from greater openness to world markets, which has fostered economic dynamism. Economists have demonstrated that the main cause of that change was membership of the EU, which brought with it gains from trade, foreign direct investment, competition and innovation.

Warwick University’s Prof Crafts says no one can know exactly how much the EU directly benefited Britain, but a 10 per cent rise in prosperity is a reasonable estimate. “That dominates any reasonable idea of what the membership fee is,” he concludes. He cautions there is little evidence that joining the bloc permanently increased Britain’s growth rate, since the EU primarily boosted the economy in the 1970s and 1990s. But leaving the union could jeopardise the UK’s gains from increased openness and competition — the contributions economists overwhelmingly say the EU has made to British prosperity.

Even economists backing Brexit rarely argue that the EU has had an overall negative effect. Arbuthnot Securities’ Ms Lea describes the bloc’s economic impact as “fairly negligible”. Patrick Minford, long one of the most outspoken economists backing Brexit, said in late February that EU membership had benefited the British economy by freeing trade.

Speaking in his factory, Nifco UK’s Mr Matthews says that during his 28 years in the car parts business, Britain’s membership has made it dramatically easier to sell products across borders while pushing companies to become more productive. That is the EU effect that has transformed not just one car-parts manufacturer in Teesside but the UK economy as a whole.

It is a modern-day fact of economic life that Mr Matthews thinks the country should not turn its back on. He wonders why Britain would even contemplate leaving the EU. “You have enough challenges in business,” he said. “Why would you put yourself in a more difficult position?”

————————-

Brexit? In or Out

The economic consequences of Brexit

Three very different outcomes of a British vote to leave the EU

What would Brexit mean for the City of London?

There is a clear split over how a vote to leave would shape the capital’s future as a financial centre

What the City stands to lose and gain from Brexit

Sectors such as foreign exchange trading have boomed during EU years

————————-

Letter in response to this article:

‘Free trade’ remains EU’s central contradiction / From Jens Munthe

Comments