Container shipping lines mired in crisis

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Deira, an 18-year-old container ship, looks serene as she steams steadily towards the Port of New York and New Jersey, the largest port on the US east coast.

But as the vessel operated by the United Arab Shipping Company nears shore, there are signs of the slump afflicting the container shipping industry.

Streaks of rust give the Deira a down-at-heel look — a reminder of many container shipping lines’ precarious financial positions. The on-deck containers, which once would have been almost all UASC’s green, are a patchwork of other lines’ red and blue boxes. This reflects how shipping lines are increasing their co-operation in an attempt to improve their weak profitability.

The industry, a vital link in the world’s supply of manufactured goods, is suffering what could well turn out to be the deepest and longest downturn in its 60-year history.

Container shipping lines have made a series of investments in new, giant vessels, and this glut of capacity has sent freight rates tumbling. The Shanghai Containerised Freight Index — one of the few public sources of information on what lines are charging to ship a container — last month reached the lowest level since its inception in 1998.

The purchasing of these huge container ships looks ill-timed, given global trade growth has been mainly sluggish since the 2008-09 financial crisis. Amid a slowing world economy, 2016 could be the fifth straight year of subpar expansion in trade.

“Over the next few years, [container shipping is] a sector that’s going to really get slammed,” says Ron Widdows, a shipping consultant and former chief executive of Neptune Orient Lines, the Singapore-based line.

Against this bleak backdrop, there are signs that the badly fragmented container shipping industry is finally starting to consolidate, in moves that should cut costs.

Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd announced last month it was in talks about a possible merger with the container shipping operations of UASC, owned by a consortium of Gulf states.

France’s CMA CGM, the third-largest container ship operator, in December agreed to buy Neptune Orient Lines for $2.4bn. Also that month, China’s two biggest state-owned container shipping lines, Cosco and China Shipping, announced plans to merge and be called China Cosco.

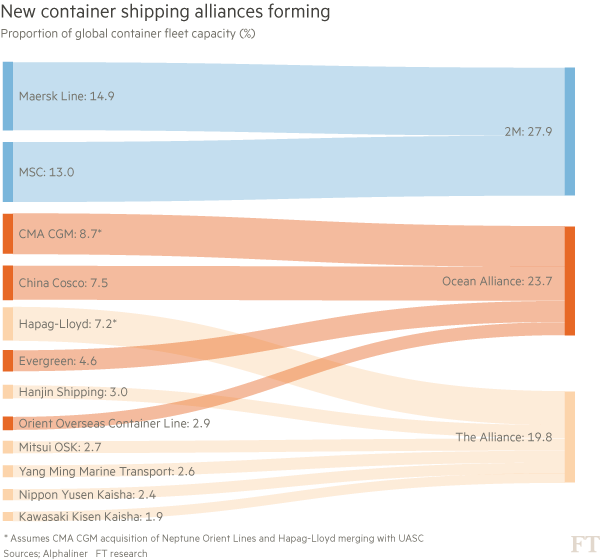

In a related development, there has also been a far-reaching shake-up of the container shipping alliances that stop short of full-blown mergers but should improve efficiency because lines can share box space on each others’ vessels.

This month, three Japanese lines — Mitsui OSK, K Line and NYK — outlined plans to form a new alliance with Hapag-Lloyd, South Korea’s Hanjin Shipping and Taiwan’s Yang Ming, to be known as The Alliance.

CMA CGM announced last month it was forming a new partnership, called the Ocean Alliance, with China Cosco, Taiwan’s Evergreen and Hong Kong’s Orient Overseas Container Line.

The partnership aims to create a stronger competitor for the P2 Alliance of Denmark’s Maersk Line and Switzerland’s Mediterranean Shipping Company, operators of the two largest container fleets.

But some doubt whether these deals and alliances will enable the companies involved to better withstand the industry’s dire conditions.

“The theory is you get economies of scale, therefore you’re better armed,” says Neil Dekker of Drewry, the consultants. “Does that work in reality? It’s an interesting question.”

Consolidation should in theory bring greater rationality to an industry that has struggled to align supply with demand.

Basil Karatzas, a consultant, predicts container fleet growth of about 6 per cent this year, while Maersk Line expects container volumes — a proxy for global trade — to expand by only between 1 and 3 per cent.

In February, AP Møller-Maersk, Maersk Line’s parent company, warned that freight rates were lower than during the financial crisis.

In the first quarter of 2016, Maersk generated $1,857 of revenue for each 40ft container it carried on its ships, 25 per cent less than one year earlier, and $203 below the average cost of moving each box.

Maersk Line’s first-quarter net operating profit fell 95 per cent to just $37m, while most other listed container ship operators recorded losses.

Their losses partly stem from how these operators have sought to match Maersk’s long-term strategy of investing in ever larger vessels which, if operated full, can significantly cut the cost of carrying each container.

The average size of ship operating on the key Asia to Europe route has grown 7.6 per cent every year since 2001, according to Drewry. The average vessel on the route last year could carry 12,560 20ft containers — three times the capacity of the Deira, which reached the Port of New York and New Jersey last week.

Mr Widdows attributes this rush for huge ships to an announcement by Maersk in 2013 that it was forming an alliance with Mediterranean Shipping Company and CMA CGM.

While China’s competition authorities blocked the alliance, Maersk and Mediterranean Shipping Company pressed ahead with co-operation.

“[Maersk’s rivals said to themselves] ‘Oh my God, we have to do something about that [alliance]’,” says Mr Widdows. “We can be more competitive with larger ships.”

In 2013, Maersk took delivery of its first so-called Triple E vessel, then ranked as the world’s largest container ship, capable of carrying 18,300 20ft boxes. Other lines are now operating even bigger ships.

But these ships only provide increased efficiency if they are well loaded. Orient Overseas Container Line reported that last year its vessels were just 72 per cent full.

Most important, there is scant evidence that shipping lines are willing to take tough decisions and remove sufficient vessels from their fleets such that freight rates rise to sustainably profitable levels.

A key test for the lines that are undertaking mergers will be whether they are willing to lay up and scrap ships.

“You need to remove some ships and then you can make the combined business profitable,” says Paul Slater, a shipping financier.

Mr Widdows is not optimistic about the industry’s future. Noting how expansion of the global container fleet is likely to well exceed “fairly anaemic” trade growth during 2017 and 2018, he says: “The next couple of years look pretty bleak.”

Comments