How to beat gender bias

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

What Works: Gender Equality by Design, by Iris Bohnet, Belknap Press, RRP£19.95 / RRP$26.95, 400 pages

Lean Out, by Dawn Foster, Repeater Books, RRP£8.99 / RRP$14.95, 88 pages

Work With Me: How Gender Intelligence Can Help You Succeed at Work and in Life, by Barbara Annis and John Gray, Piatkus, RRP£9.99 / St Martin’s Press, RRP$17.99, 272 pages

When they were younger, my children used to love telling riddles. They were particularly fond of one that went as follows. A father and son are in a car accident. The father dies and the son is badly injured. He is taken to hospital, where the surgeon cries out: “I can’t operate on him; he’s my son!” How can this be?

Even in the 21st century, this riddle proves insoluble to most people. The answer, of course, is that the surgeon is the boy’s mother.

My children, like many of their generation, would vehemently reject any accusation of sexism, but the fact that even among their age group so many assume the surgeon is male shows how persistent unconscious gender bias is. It is also one of many readable examples with which Iris Bohnet, professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, peppers What Works: Gender Equality by Design. They are part of an onslaught of information to persuade readers that, despite the best will in the world, we still behave in a biased way and this affects how well we work together.

Bohnet backs up her assertions with behavioural science, drawing on recent research such as Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) to make the point that, at work as elsewhere in life, our behaviour is governed far more by unconscious reflex than rational decision-making.

She kicks off with the example of orchestras. Making musicians audition behind a screen, a measure first introduced by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the 1970s, resulted in a big increase in the number of women players taken on. Other examples from the US, India, China, the UK and elsewhere paint a picture of a world still in the grip of gender stereotypes, where women trade being seen as likeable for being regarded as competent.

Women who ask for better pay, says Bohnet, violate gender norms in most societies, a finding that Jennifer Lawrence, the Academy Award-winning actress, would back up. When a journalist revealed last year how much less she was paid than her male co-stars, Lawrence wrote: “I would be lying if I didn’t say there was an element of wanting to be liked that influenced my decision to close the deal without a real fight. I didn’t want to seem ‘difficult’ or ‘spoiled’ . . . until I saw the payroll on the internet and realised every man I was working with definitely didn’t worry about being ‘difficult’ or ‘spoiled’.”

Since our biases are unconscious, we find it difficult to acknowledge them. I have just taken a test that Bohnet uses in the book, Harvard’s implicit association test, which, much to my disgust, says I associate men with careers and women with families. “Very frustrating”, was what I marked in the box to record my reaction.

So how can we overcome these biases? What Works joins an increasingly crowded field of literature that seeks to address this question. In recent years, Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In and Anne-Marie Slaughter’s Unfinished Business have both focused on why women are still less successful in the workplace than men — and propose solutions to match their interpretations. For Sandberg, the key to “having it all” is for women, with the support of men, to take responsibility for aspiring to the top jobs. Slaughter — by contrast — argues that the status quo makes it impossible to combine work and motherhood satisfactorily and that it is the world of work that needs to change.

Both Lean In and Unfinished Business moved the debate on from consciousness-raising about gender inequality at work to potential solutions. Yet for some, the “corporate feminism” of writers such as Sandberg misses the point. One is London-based journalist Dawn Foster, the title of whose book, Lean Out, makes it clear with whom she takes issue.

Foster argues that only by removing the structural obstacles to gender equality will we change behaviour in the long run, and she provides many examples of what she means. The increasing prevalence of zero-hour contracts in the UK, the cutting of child benefit if you have more than two children (unless you have twins or are raped), the scaling back of domestic violence services — all are backward steps for women’s empowerment.

There are good arguments to be made that addressing the lack of women at the top of organisations — Sandberg’s focus — ignores the needs of women at the bottom. But Foster chooses outrage over persuasiveness and her tone risks alienating all but those who already agree with her. The Sunday Times Rich List, she says, is “nauseating”; a “stench” of entitlement hangs over Canary Wharf, London’s financial hub; if you “[dare] to show a flash of real emotion at work . . . your income and security is at risk”. This is a shame, since there is a strong counterargument to be made against “corporate feminism”. But less simplification — particularly of Sandberg’s message — and more solutions would give Foster’s more authority.

If we are to opt for a more gradualist approach to tackling gender bias, then perhaps the place to start is better communication. This is the contention at the heart of Work With Me, a book co-authored by John Gray, known for the hugely successful 1992 bestseller Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus, and Barbara Annis, a writer and adviser on gender issues and emeritus chair of the Women’s Leadership Board at the Harvard Kennedy School — the same stamping ground as Bohnet.

Why, ask Gray and Annis, has the proportion of female chief executives in the US — just 3 per cent in 1996 — barely budged? Their answer is that men and women’s brains are wired differently and that they communicate, and thus work, in extremely different ways.

To address this, mandating change or revising recruitment practices are simply inadequate. Instead, companies must become more “gender intelligent”, a goal achieved through “educating men to understand the unique value that women bring to the table and educating women as to the reasons why men think and behave as they do”.

This appears to involve workshops and a lot of talking. But while Gray and Annis provide many illustrations of how differences in the ways men and women communicate lead to misunderstandings and setbacks in the office, there are few examples of how such problems have been overcome. Practical solutions, as is so often the case in this field, are in short supply.

In What Works, Bohnet’s approach to the question of how we should tackle gender bias begins with a recognition of just how hard this is. She quotes experiments suggesting that the more biased you are, the more difficult it is to change your views, even if you are provided with information to help you to do so. “Put bluntly,” Bohnet says, “changing behaviour means work that the vast majority of us are not motivated to do.”

The answer, she suggests, is not to be found in diversity training programmes or other similarly well-intentioned initiatives. Training can backfire: in some cases, research shows, such programmes are actually associated with a drop in the likelihood that under-represented groups become managers.

Bohnet is also scathing about self-evaluation and argues that, since women tend to be more self-critical than men, it can lead to lower performance ratings and thus worsen the gender pay gap. “I have not come across any evidence suggesting that having people rate themselves yields any benefits for themselves or their organisations,” she says.

Instead, she advocates changing environments rather than mindsets. “Small design changes”, she says, are an effective way to alter behaviour, citing the example of hotels that, rather than trying to persuade guests to switch off the lights on leaving their rooms, introduced key cards which do so automatically. Bohnet is particularly convincing on the power of data in identifying and addressing gender inequalities.

At Google, for example, women were twice as likely to quit than the average employee, but analysing the figures led Google to discover that it had a “parent gap” rather than a “women gap”. More generous maternity and paternity leave policies appear to have eliminated it. All Google employees now answer five questions shown to be the most relevant in predicting whether they will leave within the next year. If the aggregate positive answers are below a certain percentage, the company knows it must take action.

Bohnet has not just studied this issue for many years. As academic dean of the Kennedy School from 2011 to 2014, she has also put some of her theories into practice. Practical suggestions from her own experience are summarised at the end of each chapter, covering recruitment, pay negotiations, performance evaluation, teamwork and schooling.

Some of the most useful are around interviews and evaluations, where our unconscious biases can be given their freest rein. On the former — as well as the obvious, such as removing demographic information from job applications — Bohnet advises that holding individual interviews is more effective than group ones; that it helps to ask all interviewees the same questions and then compare answers across candidates; and that scoring answers brings benefits. Much of this will be unpalatable to interviewers, but Bohnet provides powerful evidence of its efficacy. She also gives pointers to software programmes available to make the task easier.

The test for a book like this is not whether it is persuasive or useful for a reader such as me, already sensitised to — and eager to take action on — gender bias in the workplace. It is whether it successfully preaches to the unconverted. You might think that a book subtitled “Gender Equality by Design” is unlikely to do this. But you would be wrong. Right up to board level, companies should find in What Works not only food for thought, but a guide for effective practical action as well.

Sarah Gordon is the FT’s business editor

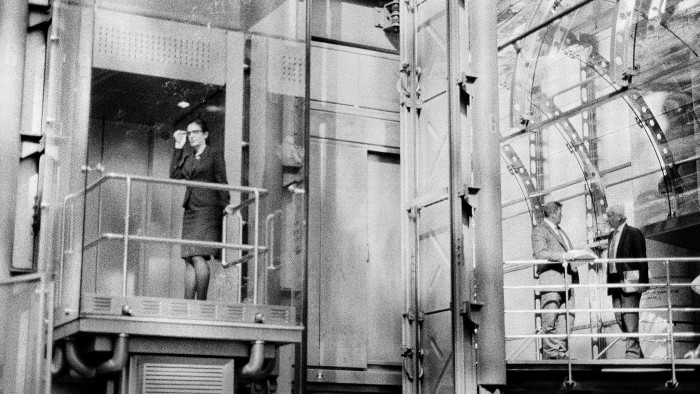

Photograph: Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos

Comments