Local chains take on coffee giants

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Not long after Starbucks made its first foray into Ho Chi Minh City in 2013, a local coffee chain called Phuc Long presented a direct challenge to the international brand.

Starbucks set up shop on a main intersection of Ly Tu Trong street in the city’s District 1. Phuc Long’s store opened a few paces away. Its logo was similarly green and white, its interiors were comparably pristine and modern and it offered its customers a considerable discount on the price of a Starbucks cappuccino. Since then, the Vietnamese chain has sought to attract other would-be Starbucks’ clients, opening in large office buildings and shopping centres across the city.

The incumbent does not seem worried. “While the food and beverage space has become very competitive in Vietnam, Starbucks has a total of 20 stores across Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi that are doing well,” says Alain Cany, country chairman for Hong Kong-based Jardine Matheson. “We plan to have 30 nationwide by the end of the year.” The Starbucks franchise in Vietnam belongs to Maxim’s Group, Hong Kong’s largest food and beverage group, founded by local businessman James Wu, in which Jardine Matheson now owns a 50 per cent stake.

Despite competition from local chains, Starbucks is perceived as a premium brand among Vietnam’s upper-middle classes. While Ho Chi Minh’s café scene is already one of Asia’s most diverse, with an abundance of independent cafés and domestic chains serving sophisticated varieties of fresh roasted coffees, there is potential for more growth.

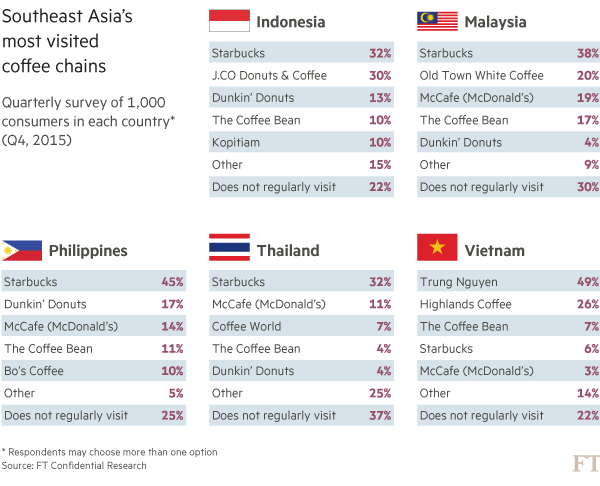

A quarterly survey by FT Confidential Research of 1,000 consumers in each of the five biggest economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (excluding Singapore) in 2015 found that Vietnam was the only country where Starbucks was not ranked as the most frequently visited chain thanks to prevalence of homegrown favourites Trung Nguyên and Highlands Coffee. FTCR gauges popular sentiment towards macroeconomic and political trends.

While the regional dominance of Starbucks and other international coffee chains has been well established, a surge in the establishment of independent cafés across Southeast Asia’s capital cities presents a long-term challenge to the bigger and better-known brands.

Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital, is a notable example, where per capita coffee consumption is growing at about 5 per cent annually, although this remains below many countries in Asean and East Asia according to the London-based International Coffee Organization.

Indonesian chains such as Coffee Toffee, Ngopi Doeloe and Anomali Coffee are multiplying, and the independent café and organic coffee concept has also developed strong roots. Similar trends are being seen in Kuala Lumpur, Manila, and Bangkok, according to FT Confidential surveys.

Independent chains are also successfully expanding in Asean’s frontier markets, including Dao Coffee Shop in Laos, Brown Coffee in Cambodia, and Coffee Circles and Espressonite in Yangon, Myanmar.

While the size of the urban middle classes in these countries remains comparatively small, Starbucks, Costa Coffee, and The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf have all made recent initial forays into Phnom Penh, while regional chains such as Thailand’s Black Canyon are expanding in both Cambodia and Myanmar.

Philippines: Fast food flourishes

Indonesia and Vietnam hold the greatest long-term potential for growth for many consumer industries targeting Southeast Asia thanks to favourable demographics and high per-capita consumption levels.

But the Philippines is still the region’s most dynamic growth market for the fast-food sector, partly because of the established dominance of local chains owned by Jollibee Foods and smaller groups like Max’s Restaurant. No other states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have homegrown fast-food chains of similar scale.

Fast-food culture has taken hold in the Philippines because of rapid urbanisation, cultural affinities with the US and the rise in many cities of outsourcing industries where staff work all night.

But there are indications that the scope for domestic growth for Jollibee has begun to plateau. FT Confidential Research, an analysis company in the FT group, conducted surveys of 1,000 consumers between 2013-15 that found the preference for Jollibee had declined slightly, albeit from a high base.

There are signs of growing competition, too, from the likes of McDonald’s, whose franchise holder, Golden Arches Development, is planning 30-40 new restaurants this year, bringing the nationwide total to more than 500. McDonald’s has been successful in tapping parts of the sector at Jollibee’s expense, notably the breakfast market.

Also there is new competition, according to Felipe Salvosa, Philippines researcher at FT Confidential. First, the push by domestic food and beverage groups such as Bistro Group, which is launching casual dining outlets across Manila, including local franchises for American chains TGI Fridays and, potentially, Texas Roadhouse and Denny’s. Then there is the growing popularity of restaurants such as Vikings Luxury Buffet, an increasingly ubiquitous feature of Filipino shopping centres that offer package deals on food and alcohol. Convenience chains such as FamilyMart, Lawson, Ministop and 7-Eleven have also expanded into cooked food. These chains now compete directly for the custom of the growing ranks of night-owl workers.

In response, Jollibee has sought to expand overseas, targeting the Filipino diaspora. It has paid $100m for a 40 per cent stake in US-based Smashburger. Jollibee has established footholds in the US, China, and other parts of Asia and the Middle East.

The chart on this page has been amended. An earlier version showed Seatlle’s Best as the second ranked coffee chain in Malaysia.

Comments